“Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?”

“That depends a good deal on where you want to get to,” said the Cat.

“I don’t much care for where,” said Alice.

“Then it doesn’t matter which way you go,” said the Cat.

– Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

It was five years ago this month that I was in Hebron, standing in a house that is no longer there. It was by far the oldest house I’ve ever seen or stepped foot into. Hebron is like that—old, ancient, with people who can say their family members have held a zip code there for 4,000 years. This is, as you may imagine, both beautiful and troublesome, because old places tend to have this hold on us, on all of us. Walk the Freedom Trail in Boston, visit Omaha Beach in Normandy, walk a bridge in Selma, stand on the Trail of Tears in Nashville, or on top of the rubbled wall in Berlin, and something within us wells up.  Maybe it’s pride or shame or something all together different. Depending upon what it is, for a moment we feel like we were there, like we made the call or pulled the trigger (or took the bullet) or swung the hammer (or didn’t). For a moment the past becomes us and we see how far we’ve come and how far we have yet to go. And this can be beautiful, and it can be troublesome, because history has a way of taking hold of our sensibilities and leaving us feeling entitled, like we deserve something for all our trouble and pain when in fact, it was never our trouble or pain. That someone else did go off to war, that once upon a time someone else did speak up in the square and get shot down for it, is part of our history and reason for gratitude and waving flags at parades. Entitlement, however, can make us think that we are better than those who suffered the defeat of battle or prejudice, that they fought in vain, which is something we would never do. Or equally snobbish, that we are the same as those who marched and won, when in fact, unlike them, we didn’t lift a finger for ally or enemy. That’s entitlement. Not having received what we believe is our fair share of credit and inheritance we do everything in our power to make others feel as if they don’t deserve it either, or worse, at all. Covering up the real and actual beauty of a people or place with labels of unwontedness, those who are entitled leave us feeling old in all the bad and unnecessary ways.

Maybe it’s pride or shame or something all together different. Depending upon what it is, for a moment we feel like we were there, like we made the call or pulled the trigger (or took the bullet) or swung the hammer (or didn’t). For a moment the past becomes us and we see how far we’ve come and how far we have yet to go. And this can be beautiful, and it can be troublesome, because history has a way of taking hold of our sensibilities and leaving us feeling entitled, like we deserve something for all our trouble and pain when in fact, it was never our trouble or pain. That someone else did go off to war, that once upon a time someone else did speak up in the square and get shot down for it, is part of our history and reason for gratitude and waving flags at parades. Entitlement, however, can make us think that we are better than those who suffered the defeat of battle or prejudice, that they fought in vain, which is something we would never do. Or equally snobbish, that we are the same as those who marched and won, when in fact, unlike them, we didn’t lift a finger for ally or enemy. That’s entitlement. Not having received what we believe is our fair share of credit and inheritance we do everything in our power to make others feel as if they don’t deserve it either, or worse, at all. Covering up the real and actual beauty of a people or place with labels of unwontedness, those who are entitled leave us feeling old in all the bad and unnecessary ways.

I never really saw it until I saw Hebron. Hebron as you may know was the first home to Abram. A man of biblical proportions, Abram (who would later come to be called Abraham) became the father to three families, all of whom would grow up to want to live under Abram’s roof, just not together. As far as families and sibling rivalries go, perhaps this shouldn’t surprise us. After all, Abram’s own family tree was speckled from the start with the unforgiving fruit of sibling rivalry.

If you believe what Genesis has to say, at the beginning of creation when Adam and Eve are sent forth from the Garden of Eden for being disobedient to God, the whole world is filled with a sense of homelessness, of not knowing where or to whom they belonged or what exactly they were supposed to do. Case in point: Cain and Abel: Adam and Eve’s own children, whose eulogy is written down just a measly four chapters into Genesis.

Born of Eve, raised by Adam, perhaps these two brothers shouldn’t have been all that different from each other, except Cain hates Abel with the hatred of a killer, for Abel is a hunter, and God it would seem favors hunters over farmers. God doesn’t say that he loves Cain any less, but when the two brothers come with offerings for God and God takes Cain’s offering ahead of Abel’s, Cain just can’t stand it. He lures Abel out into a field, away from home and even God he thinks, and there Cain kills him. It’s the start of a tragic history that no family member to come seems able to undo.

Cain kills Abel, their great-grandson Noah spawns a stream of sons who commit all kinds of unspeakable acts, and before anyone can say, “Lord have mercy,” God is already saying, “I’m going to wipe the whole slate clean.” So God sends an unspeakable amount of rain to flood the earth where the only people spared are Noah and his family, because this is how God works—there is justice but there is also grace to mediate the justice. But Noah and company will still have to get on a boat and drift to wherever the wind of God takes them. When the wind and waves finally die down and they step out onto dry ground again, they are homeless. God props up a rainbow in the sky as a reminder that never again will God wreck the earth with a flood. (Curious to me, Genesis reports that God uses the rainbow not so much as a reminder to Noah but as a reminder to God, as if God knows that having hacked off the world once, God might be permanently prone to doing it again. Apparently even the Divine is vulnerable to entitlement and the devastation of acting like the world belongs to me and is mine to do what I want with. The rainbow serves then both as God’s self-imposed restraint against being God in any way that doesn’t protect creation and human dignity and God’s promise to go on with us no knowing full well that before time is up we’re likely to give God a thousand more reasons to kill us than to love us.)

Naturally, upon disembarking the ark Noah’s family takes a head count, clamors together, and comes up with a plan that will ensure their posterity. Their new home will be a great city with a tower reaching to the heavens; safe, proud in appearance, and full of people who look, live, and sound all the same way. It’s not an insidious plan carved out of some blatant prejudice on anyone’s part but when God sees things taking shape God decides to shake things up again. This time there is no flood but God topples their tower and scatters the people across the earth to once again be homeless. Out of all this moving about, all this not knowing where or to whom they belong or what exactly they are supposed to do, God finally calls a man named Abram.

“Go,” God tells him. “Go from your family and your father’s house to the land that I will show you. I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you, and make your name great, so that you will be a blessing. I will bless those who bless you, and the one who curses you I will curse, and in you all the families of the earth shall be blessed. Just look toward heaven and count the stars, if you can. So shall your descendants be.”

Now there is something we need to understand, because without this everything that happens from this point forward in the story of Abram will seem hopeless. We need to understand that the only way to truly live greatly is by learning to love specific people. In his book, The Dignity of Difference: How to Avoid the Clash of Civilizations, Rabbi Jonathan Saks observes that we don’t come to love by deciding to love people generally. We love and are loved by the decision to love particular people at particular times in particular places—the mean kid on the playground at lunch, our spouse after a hard argument on our way out the door to wo rk, the friend who disappointed us by not showing up when we needed them to. “There is no road to human solidarity that does not begin this way” (p. 58). “I will bless those who bless you, and I will curse those who curse you,” God told Abram. In other words, this is love: we give and receive blessing from each other and it’s like receiving from the very hand of God. Of course sometimes we get it wrong and we curse each other instead, and God is in that too.

rk, the friend who disappointed us by not showing up when we needed them to. “There is no road to human solidarity that does not begin this way” (p. 58). “I will bless those who bless you, and I will curse those who curse you,” God told Abram. In other words, this is love: we give and receive blessing from each other and it’s like receiving from the very hand of God. Of course sometimes we get it wrong and we curse each other instead, and God is in that too.

It’s not unlike an experiment, and for God, if there is any chance of getting the experiment right—of the world learning to love again—Abram is going to have to move to a new land, to a place he’s never been to or heard of before. Because as life post-flood had already proved, if left to our own devices we’ll build a house and fill it only with the people we know we’ll like and who will like us back, people who speak our language and listen to our music. But that won’t fill the house with love. It won’t make for a home. To find a suitable place for a home Abram must go then to a land that only God can show him. That land is Hebron. “So Abram moved his tent, and came and settled by the oaks of Mamre, which are at Hebron” (Genesis 13).

If oak trees were to be Abram’s sign that he’d arrived in a land of new possibilities, I couldn’t find any in Hebron. Like ancient cities of its kind, Hebron does have a city wall that runs all the way around it. I like to imagine that back in the days of Abram the gates to those city walls stayed open all the time so travelers and strangers passing by Hebron who might have needed a resting place could just come in and receive some of that blessing from the hand of God. Today the city gates are locked and manned with soldiers holding semi-automatic Uzis. The soldiers are Israeli-Jews. They don’t actually live in Hebron, but they want to. To them Hebron is home, for they are Israelites, direct descendants of Abram. Those who live in Hebron are Muslim and Christian Palestinians, who much like the Israeli soldiers, know themselves to be children of Abram too. Hebron is home to them as well. Their family has had a Hebron zip code for 4,000 years.

Now some have said this is the way it’s always been. It’s Cain and Abel still fighting in the field on the edge of town, unwilling just to go back home and make up. Some have said it’s the way it needs to be, that Israeli soldiers need Uzis to protect themselves against Palestinians who might fire a rocket at them. That it’s not reasonable to expect the city gates to stay open all day; that the land belongs to Israel. It’s biblical, it’s divinely ordained, it’s politically correct, and free-roaming Palestinians are not allowed. This is the way it is and this is the way it’s going to be. At the same time, the Palestinians say they were there first and have been there all along. If God is humane, what right does the State of Israel have to move in, to lock their city gates, to say when and where Palestinians can go in their own home? Is that the way of God? What is so biblical about dispossession and slavery?

Not many people travel to the Middle East today and go to the city of Hebron. This is especially true for visitors from the United States. I find this unfortunate and unsettling, because according to the U.S. State Department, approximately $3.1 billion will be given to Israel in 2016 for the purpose of security and defense (state.gov). Of the top 25 countries who will receive a piece of the $37.9 billion being given in foreign aid this year by the U.S., Israel ranks second. Palestine does not make the list (foreignassistance.gov). I am not a diplomat or a politician or a soldier, but I’m sure they would all tell me that necessary to our own national security, the U.S. must continue to support the building up of Israel’s borders and statehood. As a U.S. citizen I am willing to concede that for reasons beyond my own scope of understanding, perhaps it is. And yet! Walls and weapons cannot make us safe. It’s true they might make us feel safe, but only for a brief shining moment. Ultimately, walls and weapons lead only to more walls and weapons, which, contrary to reports and appearances, are not signs that we are indeed safer,  but rather that we are more afraid.

but rather that we are more afraid.

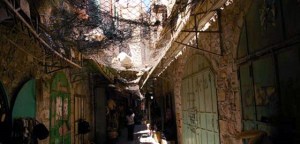

So it is that in Hebron the buildings are built very close together, making the streets very narrow. As you stroll the streets, over your head, everywhere you go, are nets stretched between the buildings and the nets are filled with trash, so much trash that in many places the nets sag to touch your head as you walk along. The nets have been put up by the Palestinians who live in the city, to protect themselves from the Israelis who stand on top of the buildings filling the nets. Now this is not the way of every Israeli or Jew living around Hebron; this much we must understand. What is more, among those who do this, they do so for reasons that are real and personal.

They’ve heard said it’s biblical, it’s divinely ordained, it’s politically correct. “There are people out there with rockets who don’t want to share their home with me anymore than I want to share my home with them. I fear them and I need to drive them out before they drive me out,” one Israeli woman told me over a shelf of oranges in the marketplace. “Throwing trash upon them, forcing them through checkpoints ought to do it.”

I don’t know but that this is not God’s vision for Hebron, for Israel, for Palestine, or for any of us. I don’t know but that it’s not biblical, it’s not divine, and it’s not politically correct. I don’t know but that many generations after Abram, the prophet Haggai (whose name aptly translates, “my holiday; my feast day”) spoke to Abram’s children and laid out a different vision, one of a different looking home. For many years the children of Abram had been living in captivity under the Babylonians. Having disobeyed the law of God by denying care to the poor and worshipping so many false idols so many times, God finally left them to their own downfall. But now, having served their time, they’ve returned home, except home isn’t what it used to be. Like a page out of the family album, their beloved Jerusalem has been destroyed and it’s temple put to ruin. Some want to rebuild it, to put it all back together the way it once was, and some do not want to do this.

“We can’t go back,” they say, “and even if we could, why would we want to?”

Onto the scene steps Haggai to announce a two-part vision for them. Part One: rebuild something. Create a space where people can come together before God in prayer, work, and praise. Because there is this idea out there that says we can somehow worship God without ever having to be with other people, that we can just sit in a field, out under the sun, and call it worship. This idea is a lie. A life lived with God is a life lived with others. For just as God is open to hearing our concerns and to carrying our sins, so must we be open and vulnerable to one another, and this means coming in from our separate places. “Rebuild something then,” says Haggai.

And Part Two: remember that the world’s silver and gold belongs to God. Remember that once upon a time God shook out the heavens and earth to bring forth all the riches of light and darkness, of oceans and mountains, and God shook out the nations too. Scattering us about like seasoning for the earth, God gives us to each other.

“So if in your rebuilding,” declares Haggai, “you must put walls around the city, don’t make them too high. And if you must have gates, keep them always open.”

For this is love: we give and receive blessing from each other, and not in any general way but in a particular way—by loving in particular those who would curse us and shut us out.

T.S. Eliot writes of a Love that both draws us in and calls us out. When this happens,

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time” (Four Quartets, V).

Eliot knows that we can’t undo what’s been done. We can’t go back to our beginning pretending as if we’ve never been there before or that we don’t know how we got there. The walls we had to climb over, the rubbled towers we had to climb out from underneath, the labels we had to rip off and the entitlements we had to cash back in so we could arrive back where we started. Going back always cuts to our core. In that place Abram is being called by God again to leave behind all his worldly possessions (everything he has worked so hard to get back!) and go off in search of yet one more world that only God can show him. In that place Cain’s hands are stained red and his mind haunted by the dead face of Abel and an age-old question: Am I my brother’s keeper? In that place Isaac and Ishmael are rollicking over an old toy they used to share when they were children, back before their mothers happened upon them. Front and center in that place, Sarah and Hagar are tripping over each other, neither of them sure of who is the victim and who is the perpetrator, but neither of them willing to admit their ignorance or guilt. In that place all our demons come knocking, all our history is laid bare and treachery looms as decisions must be made about our future. Will we head right back to where we’ve already been to do what’s already been done, or will this time be different? Like raking up autumn leaves in April, we gather together what winter couldn’t kill after all. Her colors are mostly black now, her surface bored through with so many holes that even a Fairyfly could find a grave to lie down in. But Ho-ho! What’s this? A spot of orange and even green!

___________________________________________

“Is this the place?” I imagine Abram asking God at least a couple times on his trek to Hebron.

How does one handle it when they don’t know where they’re going and therefore has no way of knowing if they’ve arrived? If the Cheshire Cat was correct in saying that if you don’t care much for where you’re going than it doesn’t matter which way you go, than I have to imagine the only thing that matters more than where we’re going is how we get there, for how we travel will have much to do with what kind of shape we’re in when we arrive, and may even determine for us whether the trip was worth the making. I’m talking about best practices. There are best practices in teaching, in business, in friendship, in dog training, in money management and even in marriage management. Now, at the risk of dismissing the benefits of good planning, best practices are usually based on a particular plan or goal we’ve laid out for ourselves. It’s helpful to know where you want to go on vacation before packing your suitcase and setting your GPS. At the same time, if our goals and plans are not reasonable to our abilities and resources, if we don’t have a car or any money with which to buy a bus or plane ticket, then no amount of best practices are going to help us get out of town.

Considering Abram, he asks no questions regarding the adequacy of the plan. We’re told that Abram is a righteous man. Could this mean that he trusts God to deliver him to wherever “there” is and to provide a little sunshine and rain along the way? That’s simple enough. But what happens if he gets screwed? Should Abram reach his end and decide he wants more and God says there is no more and this is enough. This is what Abram will do well to spend his journey preparing for—how to handle the blessed curse of a God who might disappoint him but never abandon him.

Ironically, a hundred generations later and this is what we who are Abram’s children have not come to terms with. Having made our own journeys to distant lands in search of worlds only God could show us, we feel screwed by divine misfortune. Where did we go wrong? Did we miss a turn?

For my part, I simply believe we need better practices. I will tell you that I support the existence of the State of Israel. I will also tell you that I am a confessing Christian who lives in the United States. I put it to you this way so you may understand that I don’t support the State of Israel because I am a Christian or because I am a U.S. citizen. Maybe this is normal talk for you, but eavesdrop on certain church pulpits, tune in to certain political campaign rallies and news stations right now and the difference between being a Christian, a U.S. citizen, and a supporter of the State of Israel is not readily apparent. But I am all three of these and I will tell you that not only are they not the same, but as soon as we treat them as if they are all the same, we’ve betrayed them all. For it is neither patriotic nor Christian to spend our money in support of an Israeli state at the expense of a Palestinian one. To say yes to the right of Israel to have borders while continuing to fund the purchase of bulldozers that take those borders right through Palestinian homes is not in keeping with the agreements made in 1948 when Israel was established as a state. At that time 750,000 Palestinians were driven from their homes and their ancestral land, many of them forced to live as refugees. It happened again in the 1967 war when another 350,000 Palestinians were sent packing (unrwa.org). I’m not contesting the right of Israel to exist as a state. I am contesting her practices in existing. I am contesting that Israel, proclaimed by her own Prime Minister to be a Jewish State, is not living up to the vision hoped for long ago by her own prophets—

“To loose the bonds of injustice, to undo the thongs of the yoke,

to let the oppressed go free, and to break every bond.

To share your bread with the hungry,

and bring the homeless poor into your house;

To cover the naked, and not to hide yourself from your own kin.

Then your light shall break forth like the dawn, and your healing shall spring up quickly” (Isaiah 58:6-7)

So what can we do to better our practices? Have weapons and walls made Israel and the occupied territories of Palestine safer and more peaceable? Has our unilateral support of the Israeli State and her Defense Forces—support that has provided Israel with the means to force Palestinians through checkpoints that isolate them from clean water, economic opportunity, healthcare and family, all resulting in undue harassment and degradation—has this type of complicity on our part made the United States safer and more peaceable? No. We’ve become criminal. We have perverted our hearts and made ill work of being Jewish, Christian, and Muslim, and we have put our common humanity at risk of ever being found again.

So what can we do? We can begin by recanting our lopsided theologies that have made for, and continue to make for, lopsided allegiances. (Now somewhere someone is reading this and perhaps wondering if I’m calling for a one-sided support of Palestine. The answer of course is no. We must reject the use of violence by Hamas as well as any group anywhere to denigrate and destroy Israel . To argue, however, that protesting the actions of the Israeli government and her Defense Force is to support Hamas is just careless and dangerous. For one thing, the U.S. gives no financial or military backing to Hamas. In addition, neither the leadership of the Palestinian National Authority nor the State of Palestine nor the Palestinian Liberation Organization, all of which have been given credence by the U.S., give party to Hamas. In their truest forms, Israel and Palestine want for each other too much to have any mistresses.) We can confess our duplicity in making ourselves look monstrous to the world at times, and we must confess how easily we scare at the site of difference. We can take our money and spend it instead on plane tickets to foreign lands where we’ll have to depend upon the kindness of strangers to show us a good time and feed us a good meal. We can buy a bus ticket to the other side of our own town. We can, a t the very least, take a stroll down our own street and dropping all pretenses, introduce ourselves merely as “neighbor.” Because past history and present circumstances aside, I imagine that when Abram arrived in Hebron it wasn’t all roses and caviar. We can assume that it looked a lot like the place he’d just come from (minus the tents and hitching posts for the camels which now had to be pounded into the ground all over again) and Abram likely asked God, “Why couldn’t I just stay where I was again?” To which I like to imagine God gazing out over the landscape, and declaring with a wry smile and an approving nod, “No particular reason. I just wanted you to see how beautiful the oak tree are here.”

t the very least, take a stroll down our own street and dropping all pretenses, introduce ourselves merely as “neighbor.” Because past history and present circumstances aside, I imagine that when Abram arrived in Hebron it wasn’t all roses and caviar. We can assume that it looked a lot like the place he’d just come from (minus the tents and hitching posts for the camels which now had to be pounded into the ground all over again) and Abram likely asked God, “Why couldn’t I just stay where I was again?” To which I like to imagine God gazing out over the landscape, and declaring with a wry smile and an approving nod, “No particular reason. I just wanted you to see how beautiful the oak tree are here.”