When I was in seminary working on my master’s degree, I had a friend there named Tom who was a PhD student. By the time I met Tom, he had been at it for several years and was nearing the end of his program; all that was left for him to do was defend his dissertation before a committee of professors, all of whom were considered experts in the fields of theological study and biblical interpretation. I don’t recall the exact title of Tom’s dissertation, only the main premise, which was, why I’ll be sharing a bunk in heaven someday with Hitler. It wasn’t a question. Had it been a question, quite possibly it would have been, why should I share a bunk with Hitler in heaven someday? The inference being either that I’m too good to have to share a bunk in heaven someday with the likes of Hitler or that there’s no way someone like Hitler is good enough to share a bunk with me, let alone to get into heaven someday. But it wasn’t a question, it was a statement. Why I’ll be sharing a bunk in heaven someday with Hitler.

I don’t know what you believe about heaven—where it is, what it’s like, how we’ll know when we’ve arrived there, or who can expect to be there. For all we can imagine about heaven, the one thing classic Christian teaching has worked hard to make clear is that heaven is not here, which means it is also not now. It is up there—in the sky, far above the clouds, a land flowing with milk and honey, where the streets are paved with gold, lions lay down with lambs, and we can be with our loved ones again. In heaven, everything that has been wrong here on earth is made right again. The broken are made whole, the hungry are fed, crying is no more, sorrow is no more, pain is no more. A new creation, the prophet Isaiah once declared it to be.

I suppose, if we think of heaven this way, it’s not hard to imagine that, indeed, it must be in another time and place. For if this world we are in now is heaven, then all we can say about heaven is, it’s the same old same old. What a blow. But if heaven is still out there somewhere, then we have reason to hope that this world in all its faded glory is not all there is. It is this hope that gets sung about in many old-time hymns. Hymns like “How Great Thou Art,” “Just a Closer Walk with Thee,” “Amazing Grace,” and “The Old Rugged Cross.”

To the old rugged cross I will ever be true, its shame and reproach gladly bear. When God calls me someday to my home far away, there God’s glory forever I’ll share. So I’ll cherish the old rugged cross, till my trophies at last I lay down. I will cling to the old rugged cross and exchange it someday for a crown.

Lyrics by George Bennard, 1912

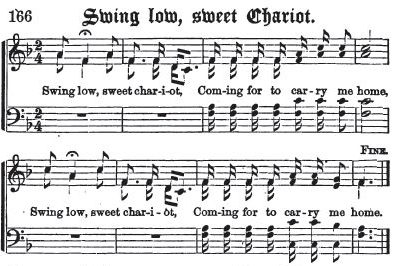

The picture we get here is of a pilgrim who is only passing through this world. For this weary traveler, the cross is a pleasurable burden, one they carry in hope of one day being able to cash it in at the gates of heaven for something richer, like a crown. Contrast this with the picture we get, however, in other hymns like “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” “Every Time I Feel the Spirit,” and “I Want Jesus to Walk with Me.” African American Spirituals, all of them first sung, perhaps, in the cotton fields of Virginia, the buses in Montgomery, and the streets of South Africa; sung by enslaved persons who looked to God not in hope of their own crowning someday, but of crowning justice and equality today.

It is curious to note that when Jesus was asked one day about how to get into heaven, the person asking the question assumed heaven to be someplace else, and those who get in to be those who are “good.”

Good teacher, what must I do to inherit eternal life?

From the Gospel according to Mark, chapter 10

The question comes from a young man who is, we are told, well-off and therefore thinks in terms of what he stands to inherit someday. However, this man has a dilemma. His dilemma is, he also thinks inheritance is subject to good behavior. Which is it? In the end, do we get what we get—some, trust funds and crowns, others, pain and poverty—because of who we came from, or because, no matter who we came from, we are good? Jesus, seeing the man’s dilemma, cuts right to the heart of the matter. Why do you call me good? No one is good but God alone. For Jesus, the answer to eternal life is not to figure out how to be good, for no one, not even Jesus apparently, is good. But lest we think this means being good doesn’t matter, Jesus tells the man, Go, sell what you own, and give the money to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; then come, follow me. What does Jesus mean by this? Was Jesus a socialist who believed only the materially poor can get into heaven? Or was he a capitalist who believed it’s possible to buy your way into heaven? Or was he both, believing that you can buy your way into heaven by becoming materially poor? I think it’s fair to say Jesus wanted this man to see what it would be like to depend upon the poor for his inheritance. To stand at heaven’s gate and realize you have nothing with which to cover your entrance fee, but that’s okay because having nothing is what gets you in.

I heard an interview once with Martin Sheen, the Hollywood actor. A devout catholic who has also been arrested over 60 times for protesting things like war and nuclearism, he was asked in the interview what brings him joy. He described standing in line every week at church to receive communion. “For the most part I stand in that line and I am so stunned to be there that all I can say is, thank you. And when the bread is handed to me, and the cup offered to me, if anyone ever asked me why I should get to have them, I’d have to look at all the other people in line with me, and all I’d be able to say is, ‘I’m with them.’”

It isn’t something that just happens, though. Just because we think we’re in with Jesus doesn’t mean we are. When Jesus tells the man who wants to get into heaven that all he must do is go sell what he owns, give the money to the poor, and come, follow me, the man turns and walks away sad. It turns out, heaven is not far away for this man after all; he is standing right on the doorstep, one step away from being in line. But he will not be getting into heaven today, and it is not because he is rich, it is because he does not want to be counted with those who get in for nothing. What a dilemma.

To stand at heaven’s gate and realize you have nothing with which to cover your entrance fee, but that’s okay because having nothing is what gets you in.

Such was the dilemma also faced by a guy named Jonah. In the whole Bible, Jonah’s story is only four chapters long. It begins with God calling Jonah to go to Ninevah. “Get up Jonah, go to Ninevah. That city has become overrun with sin and wickedness. Preach your best judgment upon them.”

Jonah, we know, was a Hebrew, and the Hebrew people had a history of being enemies with the Ninevites, and so this should have been an easy assignment for Jonah. Heck, bringing judgement down upon your enemies should be an easy one for anyone. Except when Jonah gets the call from God, rather than go to Ninevah, Jonah gets on a boat and heads away from Ninevah. And why? It’s simple really. Jonah is a Hebrew, which means that in addition to belonging to a country and having a national identity, he also belongs to God. As he tells his shipmates, “I worship the Lord, the God of all creation,” which means Jonah’s god is not only Jonah’s god but also the God of all creation, who must care not only for Jonah and the Hebrews but also for the people of Ninevah. So Jonah doesn’t go to Ninevah. How can I go to Ninevah and preach that I’m #1 when I know that’s just not true? God has a way, though, of turning even the proudest heart, and when Jonah does eventually arrive in Ninevah to preach his sermon, and the congregation hears it, they change their ways. They turn from evil to God, and God, God of course turns to them. And Jonah turns away from the whole thing. He goes out of the city and finds a lonely hillside to sit on all by himself, and there he sulks. I knew you wouldn’t go through with punishing the people of Ninevah, God! I just knew you wouldn’t. You who are slow to anger and abounding in love. But if you weren’t going to do it, why did you bring me all the way out here to say you were going to?

Jonah never receives an answer to his question. The story of Jonah just ends rather abruptly, with God asking a question and Jonah left having to think about it.

“Should I not be concerned about Nineveh, that great city, in which there are more than a hundred and twenty thousand persons who do not know their right hand from their left and also many animals?”

Jonah, chapter 4

In other words, if it bothers you that I care so much about the people, you’re going to love the fact that I care just as much about the animals.

For all the folklore surrounding the story of Jonah, it is, in the final analysis, a story with great practical implication. One can think of Jonah when they think of any number of issues we face today as a society. Like, what does our care for the environment say about our care for others? As people, do we think critically about our view on heaven, where it is and who we expect to find there? And, how does our view affect our daily compassion towards those whose religion, faith, behavior, or morals are different from our own, those whom we don’t expect to share a bunk with in heaven someday?

I thought of Jonah this past week when I was at my local library. I sit on the Board of Directors at the library and as part of our monthly meeting we were discussing the impact efforts to ban certain books from public libraries has had on our communities. As complex and politically charged as this issue has become in so many towns and cities, one board member reminded us that book banning isn’t really about books. Good parenting has always meant being involved in our children’s lives, including knowing what they are and are not reading. But banning books really isn’t about good parenting, or good books for that matter. It’s about who gets to decide which stories get told alongside our own. As the Nazis did in Germany during World War II when burning books was a way to keep people from imagining any other world than the one Hitler wanted for them— a world of hateful exclusion, of death and destruction.

But banning books really isn’t about good parenting, or good books for that matter. It’s about who gets to decide which stories get told alongside our own.

Jonah didn’t want to go to the people of Ninevah. He didn’t want to risk finding out that in the heart of God, his story and their story are inextricably bound together by love and mercy. That God found a way in the end to get Jonah to Ninevah anyway is, in and of itself, an act of love and mercy. For God would have us find out that there is a bunk, a resting place, out there in the world today and—surprise-surprise!—room even for us.