In recent months, we have all seen the death and destruction wreaked by Hamas on Israeli citizens. What has been done is tragic and inexcusable by any standard of humanity. I have nothing but sorrow. We have been reminded once more that anger is powerful, and violence only leads to violence.

When staring into the face of the pained and dead it is only natural to ask: who did this to you? Then, if there is an answer, even a faint one, we take our place alongside the victims. For who would ever want to be accused of keeping company with the victimizers, especially when the evidence of their deeds is still lying warm in the streets? No, we know what we must do to avoid any appearance of impropriety: decide who the enemy is, and should you see them, especially them, lying hurt and bleeding in the street, go around them. If you really want to try your hand at being a good Samaritan, just know this: it will come at a great cost to your own safety and reputation. You may wind up being counted among the guilty.

And yet, who is the enemy? We must be careful to decide. Those who are familiar with the story of the Good Samaritan know it to be a story of decisions. When someone lies dying and bloodied in a ditch, how do you decide on whether to stop and help them? Some conclude quickly that the person deserves what they got. They were in the wrong place at the wrong time, and should have known better. The tattoo on their arm, the label on their clothing, the hue of their skin, the cut of their hair confirms it for you. They’re in your part of town and no amount of personal or professional obligation could make you their helper, let alone their neighbor. They are the enemy, the reason you—so inconvenienced—must find another way home. That a Samaritan stops to help is shocking because Samaritans were considered the enemy. Categorically outcasted in every way, we simply don’t ever expect to be helped by our enemies. It is much easier to think of them as the people who would blow us up, and so we must blow them up first.

I visited the Middle East many years ago now. I remember vividly the feeling of walking through the streets of Hebron. One of the most ancient towns in the region, it was once home to Abraham, that great tree from whom Jews, Muslims, and Christians all take their life and grow their branches. The cobblestone streets were filled with Palestinian women selling their wares, while men sat nearby on grain sacks, their backs perched against buildings strong but sagging with time, bantering and smoking the day away. Up and down the streets, like mice scurrying underfoot, children kicked soccer balls. And every 5 or 6 feet there would be an Israeli soldier holding a machine gun. I thought then, as I think now, that people who carry guns without need of food are the most scared people in all the world. And yet, fear is not without its reasons.

Modern day Israelis know that not even a century has passed since their grandparents were living in Germany, Poland, Yugoslavia or some other European homeland, peaceably tending to life when one day their windows got smashed. Running to get under the floorboards in the kitchen, not everyone made it. Pulled outside, yellow stars sewn on their jackets like a breast plate, they were stacked on trains bound for Auschwitz, Buchenwald, Birkenau. Not a one was tried but 6 million plus were still found guilty. And of what? Of being someone; of being Jewish. Those who survived the gas chambers and death marches still came out wounded, to be forever haunted by ghosts.

Meanwhile, the rest of the world reeled from their own brand of guilt over not having stepped in sooner to stop the massacre, over having to realize the answer to the question—who did this to you?—was now, we did, we did this to you.

For the Jewish Holocaust survivor, returning home was both dangerous and unpopular. The War was over but prejudice and bigotry would not be defeated so easily. In time, The United Nations, that global symbol of goodwill and good intention, would give these millions upon millions of refugees a new home. A sliver of Mediterranean land about which prophets once said, milk and honey will flow. And they will not hurt or destroy on my holy mountain. What could be more promising and perfect for a people who have just come through hell than to settle in a place where nothing and no one can hurt or destroy? So became the official State of Israel.

And yet, along with a thousand hopes and fears, the scars of near extinction remained. In the new land of Israel were also Abraham’s other children. Palestinians. Mostly Muslim, some Christian, together with the Jews, they were like the stars in the sky. A galaxy of lights that could give warmth like a bidding fire, welcoming the neighbor in, or spew its heat like a .22 caliber, perched in the window and aimed across the street, never to trust their neighbors again.

That the State of Israel has controlled the borders in and out of Gaza and the West Bank for decades, keeping their neighbors in check at all times, tells us something about how powerful memory is, and the fear it kindles. I can only imagine what it is like to be an Israeli today. To live in dread that what the world did to your grandparents in the fatherland of Germany is now happening to you in the motherland of Israel. The Israeli solider I encountered in Hebron years ago is no longer there. I am sure, though, that another one, machine gun in hand, has come along to take their post, and that is of little wonder.

But fear of our neighbors also kindles oppression and desperation for our neighbors. Which is to say, as sick, twisted, and reprehensible as what Hamas did to Israel is, it did not happen in a vacuum. To whatever degree rocket launching and gun slinging appears random, indiscriminate and unprovoked, it may also appear to happen in a vacuum. Except, nothing happens on its own.

When the State of Israel began, it was weaned on land that Palestinians had already been existing on for centuries, though they were not a state themselves. They were subjects of British colonization. Not foster children, not even adopted children, Palestinians have persisted on the hope of one day just not being subjects anymore. Then, with the founding of Israel, they became subjects all over again, and that’s how it remains to this day. I can only imagine what it is like to be a Palestinian. The frustration and desperation that comes from being walled-in and occupied by another because they deem you a threat. No question, the tactics and thinking of Hamas is disgusting. That the majority of Palestinians believe they are disgusting is worth noting, as is the fact that they can imagine what drives them to extremes.

Yes, there has always been some measure of talk on the part of the world about helping to foster a two-state solution, Israel and Palestine living side-by-side on the map as equals. I don’t know if any two-state solution is ever going to happen, or even be possible. I do know that, as with anything, solutions begin with having the right ingredients, for you get what you put in. So Israel could choose now to act justly and reject vengeance. This would be a start. Justice doesn’t turn a blind eye to what has been done. It takes account, but stops short of thinking that the only way to guarantee your own safety is to obliterate everything and everyone who reminds you of your enemies. Justice would never kill children.

The United States, the “most powerful nation on earth,” could show up not just on the side of Israel, but on the side of the vulnerable, which would mean showing up in Gaza. If we’re going to provide tanks and guns for people to go to war with, we must also be prepared to stand in front of those tanks and guns when they are pointed at innocent lives. How powerful that would be.

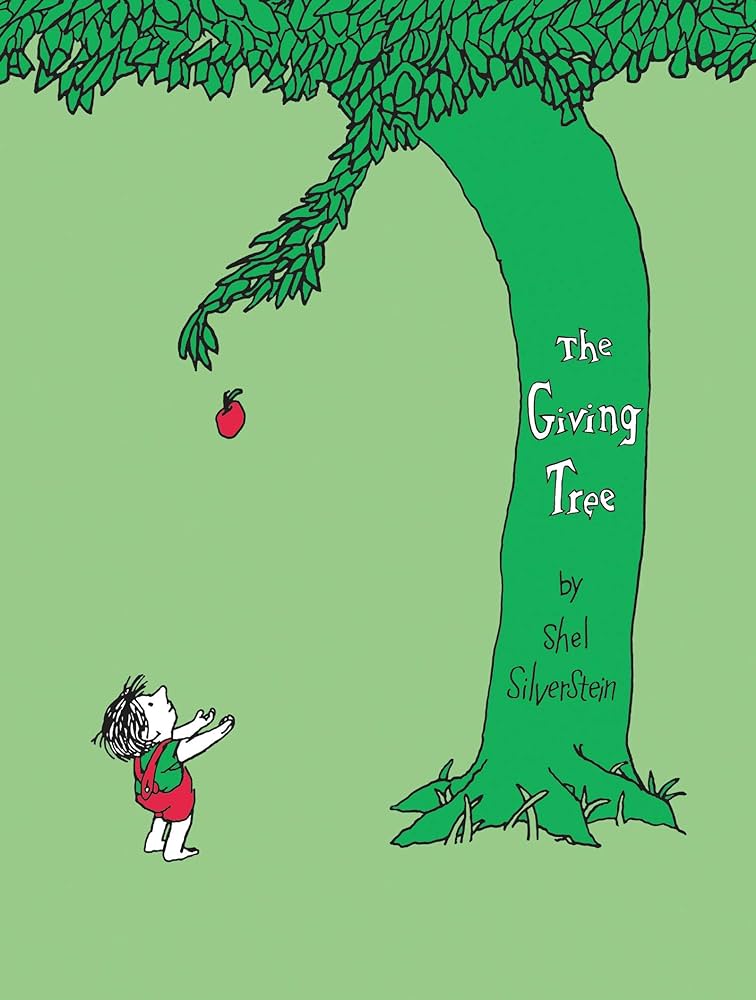

Our faith communities can reject the dualism that says supporting Palestine means being anti-semitic, or supporting the existence of the State of Israel is anti-Muslim. It is not un-Christian to love your Muslim and Jewish neighbors as you love yourself. We all come from the same tree.

And we can all agree that we have done this to each other. We have insisted on choosing between Israelis or Palestinians, war or peace, Jew or Muslim [insert a thousand other binaries here], and so we have left ourselves no option but to walk down only one side of the street. But every street has two sides; every border has two sides; every person has two sides, and crossing over is as simple as choosing to do so. Because unless we cross to the other side, nothing, nothing, nothing can ever be made whole. And wouldn’t whole be wonderful?