If Mr. Newton was correct, what goes up must come down. Go ahead, test him on it. Pull out whatever is in your purse or pocket, toss it to the air and see if it all doesn’t come down. Short of a feather, things are made to hit the floor hard and quick. A feather will also reach the floor, it will just take a little longer to get there.

Granted, this isn’t a theory we really need to test out. The fact that you are probably sitting right now and not floating on the ceiling should be enough to tell us it’s true. The way in which children, swinging from the monkey bars, let go and fall so effortlessly to the ground; the way in which food travels from the mouth, down the esophagus and into the stomach; the way our bodies and body parts sag into our later years; all proofs that everything which goes up must come down.

Scientifically speaking, we call this gravity, nature’s guarantee that we stay in place where we belong. As my mother used to say to us kids when we’d ask if we could sleep in the trees, if God wanted you to sleep in the trees, he would have made you a bird. My mother’s point being that it would be unnatural for us to think we could stay up in the air if, God forbid, our branch broke off or a stiff wind came along to blow us off or, just as horrible, the whole tree went over, taking us with it. You don’t have wings and you don’t bounce, my mom would add.

Of course, even things with wings eventually must come down. Planes, hot-air balloons, and skydivers all must land back on the ground. They cannot stay above the clouds forever. Birds must come to the ground from time to time to get their food, foraging through the forest or some stray picnic basket on the beach. If their wings are working properly than their landing will be graceful and smooth. If not, if their wings are broken, or the bird (or plane if you must) were to experience a mechanical failure, then not even wings may be enough to save them. In that case, we call it a crash. You see, everything which goes up must come down. It’s only natural.

On the other hand, not everything that comes down necessarily goes back up. How many have looked with sadness on the famous Sycamore Gap Tree that was cut down in England last week? For over 300 years the tree came to be a symbol of beauty and strength along Hadrian’s Wall. Now it has been cut to the ground by someone who had neither right nor reason to do so.

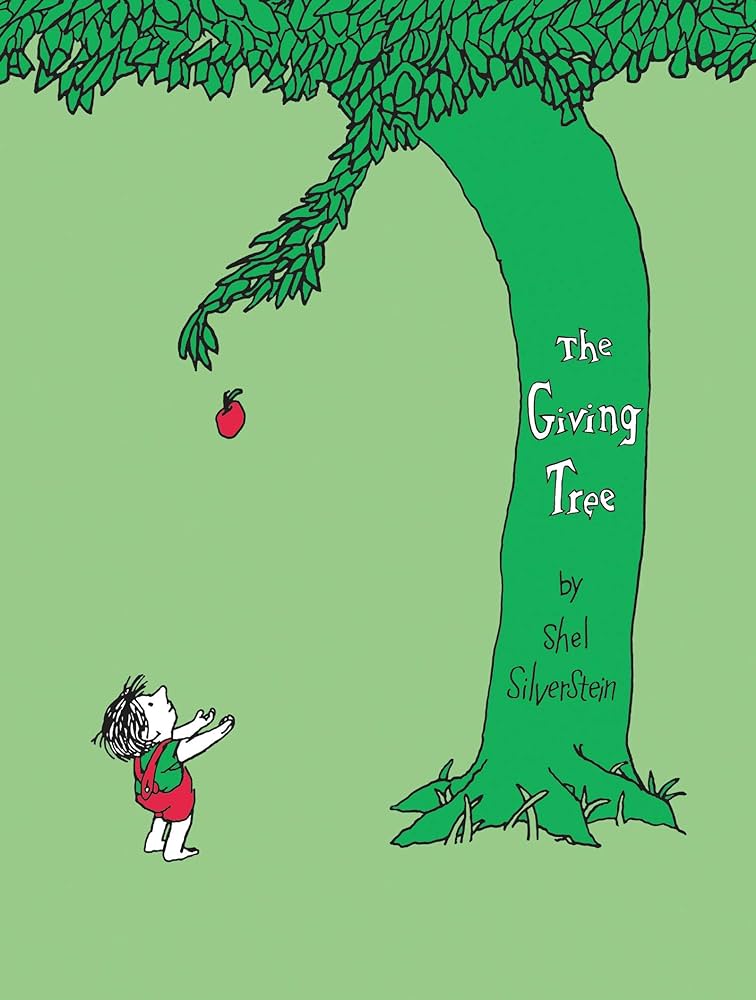

Contrast this with Shel Silverstein’s Giving Tree. In The Giving Tree, a tree, we are told, loves a little boy, and loving this boy, the tree tells him he can cut off all her branches and level her to the ground just so he can build himself a boat and a house. These are the things the boy believes will make him happy, and the tree only wants the boy to be happy. So the boy cuts down the tree and builds his boat to travel the world. He builds his house and gets married, but still, he is not happy. In the end, the boy, old and tired, comes back to the tree one day, only now he no longer believes happiness is really real. Meanwhile, the tree is still looking to give him something that might, finally, make him happy. Except, now just a stump, she worries she has nothing left to give him. How glad she is to discover that the boy, perhaps weary from searching, doesn’t want for much. Come, sit down and rest, the tree invites him. And the boy does, we are told, and the boy is happy, and the tree is happy. Though we are left to wonder if—for someone who has fallen in and out of happiness his whole life—we are left to wonder if this time really will be different. Will the boy truly stay happy? Will the tree?

The story is both tender and difficult, reminding us that we need to be careful with our actions, because love without boundaries has consequences. Love that gives itself away at all costs will get cut down in the process, just as love that wants it all without cost will also get cut down, with each being left only to sit and hope that what remains will be enough.

Such is the kind of love Saint Paul once wrote to a small band of saints in Philippi about:

If, then, there is any comfort in Christ, any consolation from love, any partnership in the Spirit, any tender affection and sympathy, make my joy complete: be of the same mind, having the same love, being in full accord and of one mind. Do nothing from selfish ambition or empty conceit, but in humility regard others as better than yourselves. Let each of you look not to your own interests but to the interests of others. Let the same mind be in you that was in Christ Jesus,

who, though he existed in the form of God,

did not regard equality with God

as something to be grasped,

but emptied himself,

taking the form of a slave,

assuming human likeness.

And being found in appearance as a human,

he humbled himself

and became obedient to the point of death—

even death on a cross.

What makes this description of love so extraordinary is that Paul says it exists in one who is God. In Paul’s world—2nd century ancient Greece and Rome—people, let alone God, didn’t move downward; it wasn’t natural. Like our world today, everything tried to move upward. Life was a survival of the fittest, a competition to see who could climb the ladder the fastest and highest. As anyone who has ever studied Greek and Roman mythology knows, there were hundreds of gods, and each god had its own distinct trademark. Among the gods, the point was to stand out, not to fit in. And power, power was a matter of showing each other, and when necessary, showing humanity, who was in charge. Poseidon could stir the seas into a tsunami; with a wave of his hand, Apollo could cover the sun and blacken the day; Aphrodite and Venus could make you fall in love, or keep you forever from it; and Zeus, Zeus with his thunder and lightning bolts, was the most powerful of them all.

If you were a human being living in this world, at best the gods were something to aspire to; at worst, something to fear. They were not, however, something to relate to. Granted, this didn’t stop people from trying. The Roman Emperor Caligula once reminded his people: “I have the power to do anything to anybody.” And though Augustus was never known to declare himself a god, after he died, his subjects did. And yet, the point may be, he still died. But what kind of God does that? What kind of God dies?

Well, Paul’s God does. And should you be crazy enough to believe like Paul, then your God does. “Only a suffering God can help,” said Dietrich Bonhoeffer from his cell in a Nazi prison camp. I don’t need a God who rises up and never comes down. Nor do I need a God who comes down only to go back up. I need a God who comes down and comes down to stay. I need a flesh-and-blood God who draws near to sit beside me. A God whose power can be seen not in the ability to control all things, but to endure all things; not to avoid suffering, but to feel it, to help heal it. A God who knows what it is to be me—someone who falls down a whole lot in this world—and who speaks my language of hope.

In her poem titled, “Gate A-4,” Palestinian poet Naomi Shihab Nye tells the following story about wandering around the Albuquerque Airport Terminal once.

“After learning my flight had been delayed four hours, I heard an announcement: “If anyone in the vicinity of Gate A-4 understands any Arabic, please come to the gate immediately.”

Well—one pauses these days. Gate A-4 was my own gate. I went there. An older woman in full traditional Palestinian embroidered dress, just like my grandma wore, was crumpled to the floor, wailing. “Help,” said the flight agent. “Talk to her. What is her problem? We told her the flight was going to be late and she did this.”

I stooped to put my arm around the woman and spoke haltingly. “Shu-dow-a, Shu-bid-uck Habibti? Stani schway, Min fadlick, Shu-bit-se-wee?”

The minute she heard any words she knew, however poorly used, she stopped crying. She thought the flight had been cancelled entirely. She needed to be in El Paso for major medical treatment the next day. I said, “No, we’re fine, you’ll get there, just later. Who is picking you up? Let’s call him.”

We called her son, I spoke with him in English. I told him I would stay with his mother till we got on the plane and ride next to her. She talked to him. Then we called her other sons just for the fun of it. Then we called my dad and he and she spoke for a while in Arabic and found out of course they had ten shared friends. Then I thought just for the heck of it why not call some Palestinian poets I know and let them chat with her? This all took up two hours.

She was laughing a lot by then. Telling of her life, patting my knee, answering questions. She had pulled a sack of homemade mamool cookies—little powdered sugar crumbly mounds stuffed with dates and nuts—from her bag—and was offering them to all the women at the gate. To my amazement, not a single woman declined one. It was like a sacrament. The traveler from Argentina, the mom from California, the lovely woman from Laredo — we were all covered with the same powdered sugar. And smiling. There is no better cookie.

And then the airline broke out free apple juice from huge coolers and two little girls from our flight ran around serving it and they were covered with powdered sugar, too. And I noticed my new best friend — by now we were holding hands — had a potted plant poking out of her bag, some medicinal thing, with green furry leaves. Such an old country tradition. Always carry a plant. Always stay rooted to somewhere.

And I looked around that gate of late and weary ones and I thought, this is the world I want to live in, the shared world. Not a single person in that gate—once the crying of confusion stopped—seemed afraid of any other person. They took the cookies. I wanted to hug all those other women, too.

This can still happen anywhere. Not everything is lost.[1]

This is the kind of world I want to live in—a shared world, a world of cookies. Do you want to live in that kind of world? Something tells me you are the kind of people who want to live in that kind of world. Something tells me you are the kind of people who can make it happen.

[1] Naomi Shihab Nye, “Gate A-4” from Honeybee. Copyright © 2008