You always barked when I came over.

Even now, I choose to believe

you were just announcing my arrival.

You were that kind of dog.

You told of the world (or were you telling off the world?)

You barked at the lawnmower,

the vacuum,

and the kids jumping in the pool.

When a certain kitchen drawer was opened,

you barked at the thought of the electric knife.

(it wasn’t even Thanksgiving)

But when I’d sit on your head, or

bound through your screen door and into the kitchen

to eat your food,

you didn’t make a sound.

You’d lift your head and just watch me go on by.

And when I’d chew on your leg

like it was my Thanksgiving dinner

(it wasn’t even Thanksgiving),

you’d let out a satisfied groan. Like you were glad

to be someone else’s sustenance.

When Dr. Lee saw the teeth marks, she asked what you’d gotten

yourself into.

You just looked up at her with your two marbly brown eyes.

Two weeks later, I had to go see Dr. Lee.

I think she understood then that life is never our fault,

only the consequence of the company we keep,

and your company liked you an awful lot.

By the time I moved in next door, you already had some friends.

Bella and BooBoo, and later, Briggs and Poo.

But you were my first friend.

I was over your house today.

They told me you wouldn’t be there.

I think they thought I wouldn’t want to go then.

Stupid humans.

Don’t they know that dogs don’t care about such things?

I let myself in like the old days.

Your owners let me go upstairs,

then downstairs,

then upstairs again.

Good people, not afraid to let me see what’s missing---

I can see why you loved them so much.

Then they let me sit there while they ate turkey sandwiches.

I tried not to bark for a bite. It was so quiet.

But what’s a dog to do? You weren’t there,

no one had announced my arrival,

and I thought they’d like to hear from you again.

Things That Come Down

If Mr. Newton was correct, what goes up must come down. Go ahead, test him on it. Pull out whatever is in your purse or pocket, toss it to the air and see if it all doesn’t come down. Short of a feather, things are made to hit the floor hard and quick. A feather will also reach the floor, it will just take a little longer to get there.

Granted, this isn’t a theory we really need to test out. The fact that you are probably sitting right now and not floating on the ceiling should be enough to tell us it’s true. The way in which children, swinging from the monkey bars, let go and fall so effortlessly to the ground; the way in which food travels from the mouth, down the esophagus and into the stomach; the way our bodies and body parts sag into our later years; all proofs that everything which goes up must come down.

Scientifically speaking, we call this gravity, nature’s guarantee that we stay in place where we belong. As my mother used to say to us kids when we’d ask if we could sleep in the trees, if God wanted you to sleep in the trees, he would have made you a bird. My mother’s point being that it would be unnatural for us to think we could stay up in the air if, God forbid, our branch broke off or a stiff wind came along to blow us off or, just as horrible, the whole tree went over, taking us with it. You don’t have wings and you don’t bounce, my mom would add.

Of course, even things with wings eventually must come down. Planes, hot-air balloons, and skydivers all must land back on the ground. They cannot stay above the clouds forever. Birds must come to the ground from time to time to get their food, foraging through the forest or some stray picnic basket on the beach. If their wings are working properly than their landing will be graceful and smooth. If not, if their wings are broken, or the bird (or plane if you must) were to experience a mechanical failure, then not even wings may be enough to save them. In that case, we call it a crash. You see, everything which goes up must come down. It’s only natural.

On the other hand, not everything that comes down necessarily goes back up. How many have looked with sadness on the famous Sycamore Gap Tree that was cut down in England last week? For over 300 years the tree came to be a symbol of beauty and strength along Hadrian’s Wall. Now it has been cut to the ground by someone who had neither right nor reason to do so.

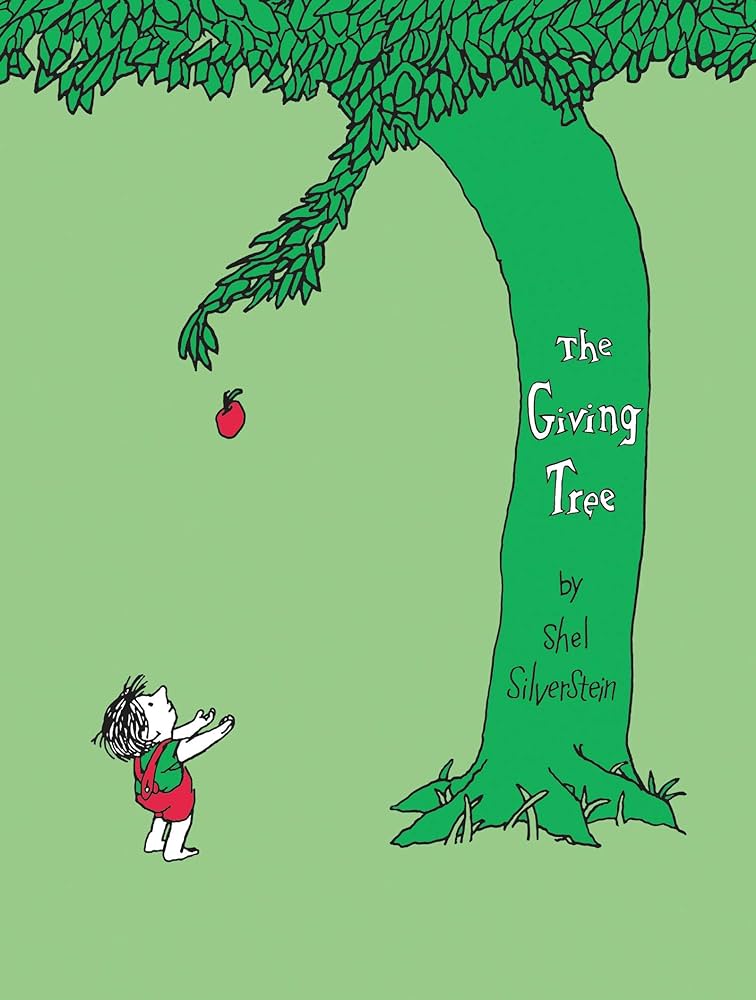

Contrast this with Shel Silverstein’s Giving Tree. In The Giving Tree, a tree, we are told, loves a little boy, and loving this boy, the tree tells him he can cut off all her branches and level her to the ground just so he can build himself a boat and a house. These are the things the boy believes will make him happy, and the tree only wants the boy to be happy. So the boy cuts down the tree and builds his boat to travel the world. He builds his house and gets married, but still, he is not happy. In the end, the boy, old and tired, comes back to the tree one day, only now he no longer believes happiness is really real. Meanwhile, the tree is still looking to give him something that might, finally, make him happy. Except, now just a stump, she worries she has nothing left to give him. How glad she is to discover that the boy, perhaps weary from searching, doesn’t want for much. Come, sit down and rest, the tree invites him. And the boy does, we are told, and the boy is happy, and the tree is happy. Though we are left to wonder if—for someone who has fallen in and out of happiness his whole life—we are left to wonder if this time really will be different. Will the boy truly stay happy? Will the tree?

The story is both tender and difficult, reminding us that we need to be careful with our actions, because love without boundaries has consequences. Love that gives itself away at all costs will get cut down in the process, just as love that wants it all without cost will also get cut down, with each being left only to sit and hope that what remains will be enough.

Such is the kind of love Saint Paul once wrote to a small band of saints in Philippi about:

If, then, there is any comfort in Christ, any consolation from love, any partnership in the Spirit, any tender affection and sympathy, make my joy complete: be of the same mind, having the same love, being in full accord and of one mind. Do nothing from selfish ambition or empty conceit, but in humility regard others as better than yourselves. Let each of you look not to your own interests but to the interests of others. Let the same mind be in you that was in Christ Jesus,

who, though he existed in the form of God,

did not regard equality with God

as something to be grasped,

but emptied himself,

taking the form of a slave,

assuming human likeness.

And being found in appearance as a human,

he humbled himself

and became obedient to the point of death—

even death on a cross.

What makes this description of love so extraordinary is that Paul says it exists in one who is God. In Paul’s world—2nd century ancient Greece and Rome—people, let alone God, didn’t move downward; it wasn’t natural. Like our world today, everything tried to move upward. Life was a survival of the fittest, a competition to see who could climb the ladder the fastest and highest. As anyone who has ever studied Greek and Roman mythology knows, there were hundreds of gods, and each god had its own distinct trademark. Among the gods, the point was to stand out, not to fit in. And power, power was a matter of showing each other, and when necessary, showing humanity, who was in charge. Poseidon could stir the seas into a tsunami; with a wave of his hand, Apollo could cover the sun and blacken the day; Aphrodite and Venus could make you fall in love, or keep you forever from it; and Zeus, Zeus with his thunder and lightning bolts, was the most powerful of them all.

If you were a human being living in this world, at best the gods were something to aspire to; at worst, something to fear. They were not, however, something to relate to. Granted, this didn’t stop people from trying. The Roman Emperor Caligula once reminded his people: “I have the power to do anything to anybody.” And though Augustus was never known to declare himself a god, after he died, his subjects did. And yet, the point may be, he still died. But what kind of God does that? What kind of God dies?

Well, Paul’s God does. And should you be crazy enough to believe like Paul, then your God does. “Only a suffering God can help,” said Dietrich Bonhoeffer from his cell in a Nazi prison camp. I don’t need a God who rises up and never comes down. Nor do I need a God who comes down only to go back up. I need a God who comes down and comes down to stay. I need a flesh-and-blood God who draws near to sit beside me. A God whose power can be seen not in the ability to control all things, but to endure all things; not to avoid suffering, but to feel it, to help heal it. A God who knows what it is to be me—someone who falls down a whole lot in this world—and who speaks my language of hope.

In her poem titled, “Gate A-4,” Palestinian poet Naomi Shihab Nye tells the following story about wandering around the Albuquerque Airport Terminal once.

“After learning my flight had been delayed four hours, I heard an announcement: “If anyone in the vicinity of Gate A-4 understands any Arabic, please come to the gate immediately.”

Well—one pauses these days. Gate A-4 was my own gate. I went there. An older woman in full traditional Palestinian embroidered dress, just like my grandma wore, was crumpled to the floor, wailing. “Help,” said the flight agent. “Talk to her. What is her problem? We told her the flight was going to be late and she did this.”

I stooped to put my arm around the woman and spoke haltingly. “Shu-dow-a, Shu-bid-uck Habibti? Stani schway, Min fadlick, Shu-bit-se-wee?”

The minute she heard any words she knew, however poorly used, she stopped crying. She thought the flight had been cancelled entirely. She needed to be in El Paso for major medical treatment the next day. I said, “No, we’re fine, you’ll get there, just later. Who is picking you up? Let’s call him.”

We called her son, I spoke with him in English. I told him I would stay with his mother till we got on the plane and ride next to her. She talked to him. Then we called her other sons just for the fun of it. Then we called my dad and he and she spoke for a while in Arabic and found out of course they had ten shared friends. Then I thought just for the heck of it why not call some Palestinian poets I know and let them chat with her? This all took up two hours.

She was laughing a lot by then. Telling of her life, patting my knee, answering questions. She had pulled a sack of homemade mamool cookies—little powdered sugar crumbly mounds stuffed with dates and nuts—from her bag—and was offering them to all the women at the gate. To my amazement, not a single woman declined one. It was like a sacrament. The traveler from Argentina, the mom from California, the lovely woman from Laredo — we were all covered with the same powdered sugar. And smiling. There is no better cookie.

And then the airline broke out free apple juice from huge coolers and two little girls from our flight ran around serving it and they were covered with powdered sugar, too. And I noticed my new best friend — by now we were holding hands — had a potted plant poking out of her bag, some medicinal thing, with green furry leaves. Such an old country tradition. Always carry a plant. Always stay rooted to somewhere.

And I looked around that gate of late and weary ones and I thought, this is the world I want to live in, the shared world. Not a single person in that gate—once the crying of confusion stopped—seemed afraid of any other person. They took the cookies. I wanted to hug all those other women, too.

This can still happen anywhere. Not everything is lost.[1]

This is the kind of world I want to live in—a shared world, a world of cookies. Do you want to live in that kind of world? Something tells me you are the kind of people who want to live in that kind of world. Something tells me you are the kind of people who can make it happen.

[1] Naomi Shihab Nye, “Gate A-4” from Honeybee. Copyright © 2008

Sharing a Bunk with Hitler

When I was in seminary working on my master’s degree, I had a friend there named Tom who was a PhD student. By the time I met Tom, he had been at it for several years and was nearing the end of his program; all that was left for him to do was defend his dissertation before a committee of professors, all of whom were considered experts in the fields of theological study and biblical interpretation. I don’t recall the exact title of Tom’s dissertation, only the main premise, which was, why I’ll be sharing a bunk in heaven someday with Hitler. It wasn’t a question. Had it been a question, quite possibly it would have been, why should I share a bunk with Hitler in heaven someday? The inference being either that I’m too good to have to share a bunk in heaven someday with the likes of Hitler or that there’s no way someone like Hitler is good enough to share a bunk with me, let alone to get into heaven someday. But it wasn’t a question, it was a statement. Why I’ll be sharing a bunk in heaven someday with Hitler.

I don’t know what you believe about heaven—where it is, what it’s like, how we’ll know when we’ve arrived there, or who can expect to be there. For all we can imagine about heaven, the one thing classic Christian teaching has worked hard to make clear is that heaven is not here, which means it is also not now. It is up there—in the sky, far above the clouds, a land flowing with milk and honey, where the streets are paved with gold, lions lay down with lambs, and we can be with our loved ones again. In heaven, everything that has been wrong here on earth is made right again. The broken are made whole, the hungry are fed, crying is no more, sorrow is no more, pain is no more. A new creation, the prophet Isaiah once declared it to be.

I suppose, if we think of heaven this way, it’s not hard to imagine that, indeed, it must be in another time and place. For if this world we are in now is heaven, then all we can say about heaven is, it’s the same old same old. What a blow. But if heaven is still out there somewhere, then we have reason to hope that this world in all its faded glory is not all there is. It is this hope that gets sung about in many old-time hymns. Hymns like “How Great Thou Art,” “Just a Closer Walk with Thee,” “Amazing Grace,” and “The Old Rugged Cross.”

To the old rugged cross I will ever be true, its shame and reproach gladly bear. When God calls me someday to my home far away, there God’s glory forever I’ll share. So I’ll cherish the old rugged cross, till my trophies at last I lay down. I will cling to the old rugged cross and exchange it someday for a crown.

Lyrics by George Bennard, 1912

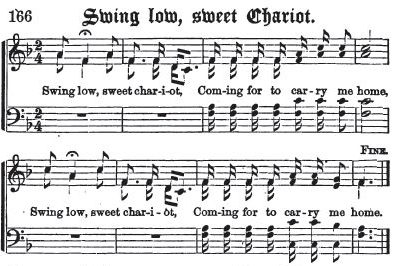

The picture we get here is of a pilgrim who is only passing through this world. For this weary traveler, the cross is a pleasurable burden, one they carry in hope of one day being able to cash it in at the gates of heaven for something richer, like a crown. Contrast this with the picture we get, however, in other hymns like “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” “Every Time I Feel the Spirit,” and “I Want Jesus to Walk with Me.” African American Spirituals, all of them first sung, perhaps, in the cotton fields of Virginia, the buses in Montgomery, and the streets of South Africa; sung by enslaved persons who looked to God not in hope of their own crowning someday, but of crowning justice and equality today.

It is curious to note that when Jesus was asked one day about how to get into heaven, the person asking the question assumed heaven to be someplace else, and those who get in to be those who are “good.”

Good teacher, what must I do to inherit eternal life?

From the Gospel according to Mark, chapter 10

The question comes from a young man who is, we are told, well-off and therefore thinks in terms of what he stands to inherit someday. However, this man has a dilemma. His dilemma is, he also thinks inheritance is subject to good behavior. Which is it? In the end, do we get what we get—some, trust funds and crowns, others, pain and poverty—because of who we came from, or because, no matter who we came from, we are good? Jesus, seeing the man’s dilemma, cuts right to the heart of the matter. Why do you call me good? No one is good but God alone. For Jesus, the answer to eternal life is not to figure out how to be good, for no one, not even Jesus apparently, is good. But lest we think this means being good doesn’t matter, Jesus tells the man, Go, sell what you own, and give the money to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; then come, follow me. What does Jesus mean by this? Was Jesus a socialist who believed only the materially poor can get into heaven? Or was he a capitalist who believed it’s possible to buy your way into heaven? Or was he both, believing that you can buy your way into heaven by becoming materially poor? I think it’s fair to say Jesus wanted this man to see what it would be like to depend upon the poor for his inheritance. To stand at heaven’s gate and realize you have nothing with which to cover your entrance fee, but that’s okay because having nothing is what gets you in.

I heard an interview once with Martin Sheen, the Hollywood actor. A devout catholic who has also been arrested over 60 times for protesting things like war and nuclearism, he was asked in the interview what brings him joy. He described standing in line every week at church to receive communion. “For the most part I stand in that line and I am so stunned to be there that all I can say is, thank you. And when the bread is handed to me, and the cup offered to me, if anyone ever asked me why I should get to have them, I’d have to look at all the other people in line with me, and all I’d be able to say is, ‘I’m with them.’”

It isn’t something that just happens, though. Just because we think we’re in with Jesus doesn’t mean we are. When Jesus tells the man who wants to get into heaven that all he must do is go sell what he owns, give the money to the poor, and come, follow me, the man turns and walks away sad. It turns out, heaven is not far away for this man after all; he is standing right on the doorstep, one step away from being in line. But he will not be getting into heaven today, and it is not because he is rich, it is because he does not want to be counted with those who get in for nothing. What a dilemma.

To stand at heaven’s gate and realize you have nothing with which to cover your entrance fee, but that’s okay because having nothing is what gets you in.

Such was the dilemma also faced by a guy named Jonah. In the whole Bible, Jonah’s story is only four chapters long. It begins with God calling Jonah to go to Ninevah. “Get up Jonah, go to Ninevah. That city has become overrun with sin and wickedness. Preach your best judgment upon them.”

Jonah, we know, was a Hebrew, and the Hebrew people had a history of being enemies with the Ninevites, and so this should have been an easy assignment for Jonah. Heck, bringing judgement down upon your enemies should be an easy one for anyone. Except when Jonah gets the call from God, rather than go to Ninevah, Jonah gets on a boat and heads away from Ninevah. And why? It’s simple really. Jonah is a Hebrew, which means that in addition to belonging to a country and having a national identity, he also belongs to God. As he tells his shipmates, “I worship the Lord, the God of all creation,” which means Jonah’s god is not only Jonah’s god but also the God of all creation, who must care not only for Jonah and the Hebrews but also for the people of Ninevah. So Jonah doesn’t go to Ninevah. How can I go to Ninevah and preach that I’m #1 when I know that’s just not true? God has a way, though, of turning even the proudest heart, and when Jonah does eventually arrive in Ninevah to preach his sermon, and the congregation hears it, they change their ways. They turn from evil to God, and God, God of course turns to them. And Jonah turns away from the whole thing. He goes out of the city and finds a lonely hillside to sit on all by himself, and there he sulks. I knew you wouldn’t go through with punishing the people of Ninevah, God! I just knew you wouldn’t. You who are slow to anger and abounding in love. But if you weren’t going to do it, why did you bring me all the way out here to say you were going to?

Jonah never receives an answer to his question. The story of Jonah just ends rather abruptly, with God asking a question and Jonah left having to think about it.

“Should I not be concerned about Nineveh, that great city, in which there are more than a hundred and twenty thousand persons who do not know their right hand from their left and also many animals?”

Jonah, chapter 4

In other words, if it bothers you that I care so much about the people, you’re going to love the fact that I care just as much about the animals.

For all the folklore surrounding the story of Jonah, it is, in the final analysis, a story with great practical implication. One can think of Jonah when they think of any number of issues we face today as a society. Like, what does our care for the environment say about our care for others? As people, do we think critically about our view on heaven, where it is and who we expect to find there? And, how does our view affect our daily compassion towards those whose religion, faith, behavior, or morals are different from our own, those whom we don’t expect to share a bunk with in heaven someday?

I thought of Jonah this past week when I was at my local library. I sit on the Board of Directors at the library and as part of our monthly meeting we were discussing the impact efforts to ban certain books from public libraries has had on our communities. As complex and politically charged as this issue has become in so many towns and cities, one board member reminded us that book banning isn’t really about books. Good parenting has always meant being involved in our children’s lives, including knowing what they are and are not reading. But banning books really isn’t about good parenting, or good books for that matter. It’s about who gets to decide which stories get told alongside our own. As the Nazis did in Germany during World War II when burning books was a way to keep people from imagining any other world than the one Hitler wanted for them— a world of hateful exclusion, of death and destruction.

But banning books really isn’t about good parenting, or good books for that matter. It’s about who gets to decide which stories get told alongside our own.

Jonah didn’t want to go to the people of Ninevah. He didn’t want to risk finding out that in the heart of God, his story and their story are inextricably bound together by love and mercy. That God found a way in the end to get Jonah to Ninevah anyway is, in and of itself, an act of love and mercy. For God would have us find out that there is a bunk, a resting place, out there in the world today and—surprise-surprise!—room even for us.

Accessing The Holy

This is a story about a parking lot.

In the first church I worked there was a woman named Maggie. Her actual name was Magnes, which is why, according to her, she asked everyone to call her Maggie. Every Sunday Maggie would come to church and sit, along with 3 or 4 other women, in the back pew, as close to the exit as anyone could get. There was something about all these women that was remarkably similar. They all had wrinkles on their hands and forehead, they all wore fancy hats, and they all walked a bit hunched over with a swagger that came from being 80-years old. Like Maggie, they also all came alone, most of them driving either a tiny Ford Escort, all that their fixed income could afford, or a Cadillac the size of a Carnival cruise ship. They drove those cars always thinking about what it used to be like to sit in the passenger seat, back when their husbands were alive and did all the driving.

For Maggie, however, there was now Gary. At the time I met Maggie, she and Gary had been married just a few years. I remember Maggie telling me plainly, “Gary was convenient.” Gary, a widow himself, could never survive the future without someone to cook and clean for him, and Maggie couldn’t survive the future without someone to pay for the food. So they got hitched. Gary’s grown daughter Suzy wasn’t crazy about the arrangement. It mostly had to do with Maggie, whom Suzy felt was only looking for an inheritance from Gary. Mind you, Suzy wasn’t mean, not at all. She cared about Maggie and about seeing Maggie cared for, and she didn’t mind her father helping Maggie out. She was also grateful for Maggie and the around-the-clock care she gave to her father, who sadly, just after getting married to Maggie, was diagnosed with cancer. What Suzy did mind was seeing her father be generous to someone who hadn’t done for him nearly as much as she—the twinkle in her daddy’s eye for 64 years—had done. Call it the plight of the Prodigal’s older sister, call it the luck of the worker who shows up at closing time and gets paid the same as the worker who put in an 8-hour day, sometimes there is nothing harder for us to take than grace when it is given to somebody else.

To make matters even harder, Maggie’s only son, Roy, whom Maggie would say, “never really had a father,” showed up at the door one day looking for a place to live, and Gary rolled out the welcome wagon for him, giving Roy, of all things, Suzy’s old bedroom to sleep in. Roy needed this grace because, well, along with Gary, he too was dying from cancer. For Roy, it wasn’t the first time. When he was just three, he was diagnosed with cancer. He fought and beat it then. But it cost him a kidney, and for the next 47 years Maggie kept telling her son, “You’re special,” and Roy believed her. I’m sure it’s what brought him to show up on Gary’s front step, and what brought Maggie, on the day Roy died, to ask me if the church would allow her son a funeral service.

He’s not a member, you know, she told me. And he never even comes to church.

I don’t think God cares about any of that, I told her.

Well, no, I suppose not, but maybe the church does?

No, we don’t care about any of that either, I assured her, half assuring myself as well.

What about his past though? Maggie added. I mean, Ray had a past.

Don’t we all, I thought. Tell me about it, tell me about Roy’s past.

Well, when he was 23, he called me up to say, ‘Mom, I’m an alcoholic and a drug user.’

I bet that was hard to hear. What did you tell him?

I told him what I’d always told him. “You’re special.” Then, I got him some help, found him an AA group to be a part of.

And did it? Did it help?

Yes, I think so. He moved around a lot—Florida to California and back to Florida. I didn’t always know where he was or how he was doing, but he was special, he was very special.

On the day of Roy’s funeral at the church, the service was at 10 a.m. At 9:30, the parking lot, which held 300 cars, was jam packed under a haze of cigarette smoke. Curious—and admittedly, a bit annoyed—I stepped outside to see what all the commotion was about.

Good morning, I said to a man standing near the door.

Oh, ah, good morning. I hope you don’t mind, reverend, it calms us down, he said, tucking his cigarette ever so slightly behind his back.

In my head, I was trying to figure out what was going on. The way Maggie told it, I figured we were going to be lucky to fill up one pew at the funeral. Are you, are you all here for Roy? I ask the man still puffing on his cigarette.

Well, we’re not here for you, he said with a cheeky grin.

If you don’t mind me asking, how do you all know Roy?

And that’s when he told it to me, the Gospel like I’d never heard it before. We all know him from being in NA and AA together. He sponsored nearly all of us. If not for Roy, most of us wouldn’t even know the word recovery. Because of Roy, we know it’s more than just a word.

At the funeral, I learned that, at one time or another, Roy had sponsored 225 people through NA or AA. One of them got up to read a story about Jesus and Matthew. What a crazy story this is.

As Jesus was walking along, he saw a man called Matthew sitting at the tax-collection station, and he said to him, “Follow me.” And he got up and followed him.

Matthew, chapter 9, verse 9

Jesus calls Matthew to follow him, and Matthew does. There are no negotiations, no promises made. Jesus doesn’t say, Follow me, Matthew, and I’ll throw in an all-expense paid trip to Bermuda. Matthew doesn’t say, I’ll follow you, Jesus, so long as you agree to pay me more than what I’m making now as a tax collector. With other disciples, Jesus at least promised that the work they’d get to do with Jesus would be both personally and professionally more fulfilling. Follow me, Jesus said to Peter and Andrew—two fishermen who weren’t very good at fishing—follow me and I’ll make you fish for people.

But with Matthew it’s a simple directive. Follow me. And Matthew does.

I don’t know what makes Matthew do it. Maybe he was tired of running the rat race, fed up with being a hatchet man. Everyday his job was to not care about whether you could afford to buy groceries or to keep a roof over your head, so long as you paid your taxes, so long as Rome got richer. It was degrading work, degrading to Matthew’s soul. But it was a runaway train and Matthew didn’t know how to get off. Then, one day, Jesus comes along and throws him a lifeline. “Follow me.” And Matthew does.

Next thing we know Matthew is throwing a dinner party.

And as he sat at dinner in the house, many tax collectors and sinners came and were sitting with Jesus and his disciples. When the Pharisees saw this, they said to his disciples, “Why does your teacher eat with tax collectors and sinners?” But when he heard this, he said, “Those who are well have no need of a physician, but those who are sick. Go and learn what this means, ‘I desire mercy, not sacrifice.’ For I have not come to call the righteous but sinners.”

verses 10 – 13

Jesus is there and all of Matthew’s former co-workers are there as well. Tax-collecting low-lifes. What can you say? If there’s nothing harder to take than grace when it is given to someone else, there is nothing greater than taking the grace you’ve been given and sharing it with others.

Of course, and this is what gives grace its name, as far as we can tell, Matthew wasn’t asking for it. He wasn’t even looking for it. Not until Jesus comes along to tell him there can be something more does Matthew even realize more exists. But once he has it, there’s no keeping it to himself.

You understand, this is not a story about a parking lot. It is about what can happen when we give each other full and equal access to holy places. And we need holy places in our world today. We need them in Morocco and in Ukraine. We need them in Washington, and anywhere else we’d like to call home. Places where hope meets us at the door and call us by our one true name. Where recovery is not just a word, but a thing we work for together. Where grace surprises us at every turn.

Little Flock

“Therefore I tell you, do not worry about your life, what you will eat, or about your body, what you will wear… For it is the nations of the world that seek all these things, and your Father knows that you need them… Do not be afraid, little flock, for it is your Father’s good pleasure to give you the kingdom. Sell your possessions and give alms. Make purses for yourselves that do not wear out…” (Luke 12).

I read an article recently about how little things are dying just as big things are getting bigger. I suppose the article could have been talking about any number of realities, but it wasn’t. It was talking about the church in North America.[1] Frankly, I find the article to be a dime-a-dozen. Regarding the North American part of this reality, one might argue that getting bigger has been the recipe from the beginning. We’ve always been getting bigger, or at least wanting to be. One of the first topics we cover in school as children, next to basic math and learning to write our name, is the explorers. Essentially, what we are after is the answer to such questions as, how did we get here? Who got here first? And where did they come from? As a fourth grader growing up in New England, my answers amounted to nothing more than a list of names and places. To Coronado we owed the southwest, including the discovery of the Grand Canyon; to de Soto we owed Texas; to Ponce de Leon we owed Florida and that elusive fountain of youth; to Christopher Columbus we owed the Bahamas; and to that hearty band of pilgrims who left England in 1620 for fairer shores, we owed everything. Am I right about this? Maybe it was just my generation, or my family and church who said that while Columbus discovered America, it was the Pilgrims, landing on Plymouth Rock in 1620, who gave us America. Fleeing the persecutions and idolatries of the Church of England, they risked life and limb to set sail for a land where they could live and worship freely, the way they wanted to. For right or wrong, this was the story of America I was told, and this is the story I bought into. As such, this was a story about an America where not just ideals and dreams are supposed to be bigger, but where God is supposed to be bigger, and where God is behind the getting bigger.

And so, it was not hard for America’s first pilgrims to regard this land as their manifest destiny, God’s divine gift to them, meant for them to have, that in having it they might also enlarge it. For a gift left untouched and unused is but a destiny left unfulfilled.

History has shown that in the early years of Plymouth Plantation, life was governed somewhat successfully by a series of treaties and compromises made between the Pilgrims and the natives, whose homeland the Pilgrims were living on. This would not change the fact, however, that, to the Pilgrims, the natives were considered savages, likened to the Canaanites they had read about in their Bibles, the ones about whom the Israelites once said, “They are giants, and we’ll never take them,” but about whom their leader Moses said, “If the Lord is pleased with us, he will bring us into this land and give it to us.”[2] We can take them, it is our manifest destiny. And take them they did. In the first 225 years of the founding of the United States, upwards of 100 million Native Americans were forcibly removed from their homes, ultimately to die from the spread of unwarranted and unmitigated disease, warfare, and genocide at the hands of those whom today most of us call our American ancestors, who believed it was their destiny to get bigger.

I don’t share this bit of history in order to make social or political hay, or to spark confrontation with anyone whose version of the story may be different. Plus, surely someone will say, you can’t have it both ways, you can’t say the church isn’t called to have a national identity and then use the pulpit to talk about America. Fair enough. I admit, figuring out how to speak of God and America in the same sentence is as complicated and complex as trying to figure out how to tie your shoes. There’s more than one way to do it, and some people just choose to wear slip-ons.

Just the same, we must reckon with the fact that, to whatever degree history gets told by the victors, in America, it was the church-goers—and by “church-goers” we mean those who once-upon-a-time dared to invoke the name of God in declaring independence for themselves—We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness—it was the church-goers who also stipulated that enslaved persons, black persons, counted as only three-fifths of a person. It was the “church-goers,” the so-called Christian missionaries, who, in the spirit of manifest destiny, landed upon the shores and moved across the frontiers, but who left in their wake trails of tears upon which Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw and so many others were forced to march from their homes to go live on reservations, reservations whose dignity to this day is threatened by poor access to healthcare, education, and corporations who would steal their land for profit. And it was the “church-goers” down south, and up north, whose houses of worship and personal fortunes were made bigger and bigger by the hands of people they would never actually allow into their churches.

Many years ago, I visited the Wren Building on the campus of The College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, the second oldest academic institution in the country. The Wren Building, constructed in 1700, is the oldest academic building still in use today. Within the building are several classrooms, offices, and a chapel. As part of the chapel there is a small balcony. I remember learning that, back in colonial days, the balcony is where enslaved persons sat, while their white masters sat down below. One might think slaves wouldn’t even have been allowed in church back then. However, their masters wanted them there, to hear the sermon. A typical sermon being one that served to remind enslaved persons that their station in life was by God’s design.

I am glad to say that if you go to the campus today, there is a memorial bearing the names of people who were enslaved by the college over a period of 172 years, some of whom, undoubtedly, built the chapel.

When we consider how getting bigger has been the way of it for America since her beginning, and how the church, for better or worse, has helped her in her quest, it should not surprise us if we, as a church, should feel a certain desire to always be getting bigger as well. I know I feel this way sometimes. As embarrassed as I may be to admit it, on both a personal and professional level, I want bigger crowds, a bigger budget, a bigger safety net. I feel better when people are asking, what can I do? Rather than, do I have to do that again? When my brain is feeling inspired, not empty. When I am not thinking about how to keep something going, because I am too busy trying to keep up. When we, with our ten thousand other things to do, couldn’t be happier to put it all down and show up to church for another Sunday. Yes, I too would like to be bigger.

But who am I kidding? If the article I read recently is any indication, only those churches that are already big are getting bigger, while the little ones are dying. Of course, the article didn’t say what constitutes “big” or “little,” leaving open the possibility, I guess, that 2 people could be considered big, and 2,000 people could be considered small.

What I find interesting is what Jesus says: Do not be afraid, little flock. At the time he said it, Luke records there were thousands in the crowd, so many people that they began trampling on one another.[3] Some were sick, so sick they were dying, and they just wanted to get close enough to have Jesus touch them. Others were lonely and wanted to get close enough to have Jesus hug them. And others just wanted to get close enough just to hear what wisdom or hope he might have to offer. There were thousands of them, and Jesus called them a “little flock.” It’s almost as if Jesus knows, no matter how big we get, we’re still just a little flock.

The truth is, we can super-size our order at the drive-thru all day long and build houses as big as old Solomon had in all his glory, but we’re still going to be found wanting. We can live to see the greatest medical achievements of all time, but there will always be something that can kill us. We can work our fingers to the bone putting food on our table, and even on our neighbor’s table, but the poor we will have with us always. We can be as big as an empire, protected and preserved on all sides, but still, we’ll be a little flock, wishing we could be bigger. So, take heed: do not be afraid, little flock. Do not be afraid for your life, what you will wear, what you will eat. For it is the nations who worry about all these things, and you are not a nation.

If we take Jesus at his word here, it would be easy to take him as reckless. Do not worry about what you will wear or what you will eat. “Man, are you crazy! Everyone needs to eat, and some already haven’t had a bite in days!” But it would be a mistake to take Jesus as saying that in this world possessions do not matter. For what Jesus says is, it is God’s good pleasure to give you a kingdom, and in this kingdom, possessions matter greatly, because in this kingdom people will sell their possessions to provide for the poor. Because in this kingdom, sharing, generosity, and human equality rule. In this kingdom, purses will be stuffed with a kind of riches that will never run out, the riches of brotherhood and sisterhood. In this kingdom, a piece of bread broken and offered in grace will be worth a feast. So, take heed little flock, and do not be afraid, there is a kingdom, God’s own, and it belongs to you.

[1] https://www.npr.org/2023/07/14/1187460517/megachurches-growing-liquid-church

[2] Numbers 13:32; 14:8.

[3] Luke 12:1

Sticking With The Weeds

He put before them another parable: “Let the weeds and wheat grow together…”

-Jesus of Nazareth, 1st century.

Jesus is preaching another parable today. Did you know there are many ways to preach? It doesn’t always have to be from a pulpit, or in some holy church or temple. The sermon doesn’t always have to have three finely tuned points, make your heart sing, or your feet to dance. For Jesus, the great majority of his sermons took place on a whim. While he was walking along the beach, or sitting on a hillside of flowers, or observing some token of human kindness, or human suffering, and he would say, You know what this is like? This is like the kingdom of heaven. And then he would go on to tell a parable, a story about how a farmer sowing seed is like heaven, or how a shepherd searching for one lost sheep is like heaven, or how an employer who pays the last hired worker on the day the same wages he pays the first hired worker on the day is like heaven, or how one person showing mercy to another person, no matter much bad blood there is between them, is like heaven. Signs so visible and ordinary to the world that if someone didn’t point them out to us as being of God, we would miss them. But point them out and everyone goes, “Oh, I get it!”

Or not.

There’s a reason Jesus told so many parables. It may have had something to do with the fact that he just liked them. Like a writer who prefers writing poetry over novels. But more likely, the reason Jesus worked in parables so much is because no one ever understood them. In fact, not only did people seem to struggle with the meaning of his parables, but the closer you were to Jesus, the more you heard them, the less you seemed to get them. Now you would think, for this reason, that Jesus might have changed up his methods, tried preaching in iambic pentameter, or setting his sermons to parody. He couldn’t have liked being misunderstood any more than his listeners liked not being able to understand. But no, he just kept right on with his parables.

We can imagine, then, that when he put before them another parable, everyone in the congregation shook their heads in dismay. “Ugh, not another parable.” We can also imagine that people might have gotten up and walked out, headed down the street to find a different preacher, one who doesn’t preach in parables but instead gives it to you straight. I mean, seriously, why does Jesus preach in parables? Hold that thought for a moment while we consider this one:

“God’s kingdom is like a farmer who planted good seed in his field. That night, while his hired men were asleep, his enemy sowed weeds all through the wheat and slipped away before dawn. When the first green shoots appeared and the grain began to form, the weeds showed up, too. “The farmhands came to the farmer and said, ‘Master, that was clean seed you planted, wasn’t it? Where did these weeds come from?’ “He answered, ‘Some enemy did this.’ “The farmhands asked, ‘Should we weed out the weeds?’ “He said, ‘No, if you do, you’ll pull up the wheat, too. Let them grow together until harvest time. Then I’ll instruct the harvesters to pull up the weeds and tie them in bundles for the fire, then gather the wheat and put it in the barn.’”

Gospel according to Matthew, chapter 13:24-30

I’m not a farmer or gardener, but one doesn’t need to be to know that this is indeed a parable, full of strangeness. For who needs to ask where weeds come from? Everyone knows they just come. No one needs to plant a weed to make it grow; they just do. And when they grow, they grow everywhere, without help, without permission, without consideration. So says the amateur. Real farmers, that is those who get up with the sun and work all day trying to grow things that aren’t weeds, know that nothing just grows. Cucumbers don’t just grow, azaleas don’t just grow, redwoods don’t just grow. Farming is a chore of daily optimism, of hard-earned faith. The farmer puts a seed—by all appearances, nothing but a speck of hard material that, depending upon the type, will cost you $10 for a thousand on Amazon—into the dark, black soil. The next morning, the farmer gets up with the sun again, only they know they will see nothing for their work from the day before. It will take dozens of sunrises and 14-hour days spent taking water from the well and pouring it on the seed before a sprout of green might appear out of the black soil. What is more, the farmer must also pray for rain, without which the well will run dry of water. No rain, no water; no water, no cucumbers; no cucumbers, no food; no food, no life. It’s a chore of daily optimism and hard-earned faith—farming. To believe the sunlight will somehow reach the seed in the darkness, that the rains will come, that in the same place where we bury our dead, new life is growing.

To have a full appreciation for the parable Jesus is telling today, and how strange it is, we must understand this: the magnitude of the farmer’s chore, and what is at stake for them, not just cucumbers but life itself. Because when the farmhands see that weeds are coming up alongside the grain, they ask the farmer, Where did these weeds come from? Most people, when they think of a weed, probably think of ugly dandelions growing up through the cracks in the driveway, but, by definition, a weed is any plant growing where you do not want it. This means a weed could be as glorious as 100 corn stalks in what is supposed to be a garden of tomato plants. Both are tasty, and on their own they will grow just fine. But together, they will compete for soil and water, and potentially kill each other on the way to survival.

In Jesus’ day, it was not uncommon for someone to sneak in at night and plant a weed in a neighbor’s garden. Farming was big business, and the way most families made their living. Planting a weed in someone else’s garden, then, wouldn’t just ruin their crop, it would ruin their future. In short, it was an act of sabotage, and an easy way to make an enemy.

Here in my little corner of New England, I don’t suspect a lot of people for sabotaging my crops. But like any good parable, the point is to get me thinking about who or what does feel like a sabotage upon my future, and my children’s future. Who or what do you consider a threat to your way of life, and look upon as an enemy? I could name them for you, but my guess is, you know them already. Their face, their address, what car they drive and how many, where they buy their coffee, how they vote, where they spend their Sunday mornings, and what it is they said or did once-upon-a-time to make you think they’re a bad seed and they should be weeded out.

We must understand this: the magnitude of the farmer’s chore, and what is at stake for them, not just cucumbers but life itself.

The thing is, weeding out the bad seed is precisely what you’d expect a good farmer to do if they’re going to protect their crop, family, and future. It’s the responsible thing to do. That Jesus has the farmer tell his farmhands to do just the opposite seems surprising, if not reckless. I mean, when you see something or someone that could cause hurt or destruction, shouldn’t you put a stop to it right away? When a splinter becomes infectious, shouldn’t you take it out? When a relationship becomes toxic, shouldn’t you get out? Even churches have protocols for telling a person whose behavior has become so contrary to their unity, it’s time for you to leave.

What is Jesus thinking, then, to say, No, leave the weeds alone to grow alongside the good seed.

It’s worth noting that Jesus’ concern really isn’t for what’s going to happen to either the good seed or the weeds if they are left to grow side-by-side. In the end, he says, both will be where they will be. The good seed will grow into wheat that will be gathered into barns, and the weeds will be gathered for burning. Jesus’ concern is with the gardener, whose tactics and disposition, he fears, are not suited for the job at hand. What if in pulling up the weeds, you also pull up the good stuff? No, better to leave both until a time when someone who knows what they’re doing comes along.

Two weeks ago, along with several adult advisors and 11 students, I spent an afternoon at NeighborWorks of the Blackstone River Valley, an organization committed to enriching community life in Woonsocket, Rhode Island. We know this, that there are pockets of every village, town, and city where invisible (and sometimes not so invisible) lines have been drawn. These lines, often separating the haves from the have-nots, always result in higher rates of poverty and crime for the have-nots. Too often, the answer to dealing with poverty and crime in America has been to weed out the poor and criminal by sheltering the first and incarcerating the second. Woonsocket is no exception. What makes NeighborWorks especially unique, however, is the way they say no to this tactic. Believing that the best hope for people is life in community with others, NeighborWorks seeks to root people by creating opportunities and resources for every individual and family to be able to afford their own house.

In a world where we have grown so quick to take sides and draw guns, it is a chore of daily optimism and hard-earned faith to not pull at each other like we’re weeds but instead to stick it out with one another. But stick it out we must, for this is what Jesus says heaven is like.

The famed Irish poet Seamus Heaney once wrote:

Human beings suffer,

They torture one another,

They get hurt and get hard.

No poem or play or song

Can fully right a wrong

Inflicted and enduredHistory says, don’t hope

On this side of the grave.

But then, once in a lifetime

The longed-for tidal wave

Of justice can rise up,

And hope and history rhyme.So hope for a great sea-change

On the far side of revenge.

Believe that further shore

Is reachable from here.

Believe in miracle

And cures and healing wells.Call miracle self-healing

The utter, self-revealing

Double-take of feeling.

If there’s fire on the mountain

Or lightning and storm

And a god speaks from the skyThat means someone is hearing

The Cure At Troy

The outcry and the birth-cry

of new life at its term.

In classic Christian theology there is an image of Jesus that comes from a line in the Apostles Creed which says, He was crucified, died, and was buried. He descended into hell. After three days, he rose again. Many have wondered at what Jesus was doing down there in hell for three days, waiting for his resurrection. I like to imagine he was pulling up all the souls of the dead who, like weeds, had been tossed to the fire for burning, gathering them once again to be side-by-side with all the other good seeds.

I honestly don’t know why Jesus insists upon telling parables—these stories that make us think the world is never as bad as it seems and hope is just that good—but thank God someone does.

Crumbs All Around!

“Jesus left that place and went away to the district of Tyre and Sidon. Just then a Canaanite woman from that region came out and started shouting, “Have mercy on me, Lord, Son of David; my daughter is tormented by a demon.” …Jesus answered, “It is not fair to take the children’s food and throw it to the dogs.” She said, “Yes, Lord, yet even the dogs eat the crumbs that fall from their masters’ table” (Matthew 15:21-28).

I would like to take as my subject a single word, FAITH.

What is it?

Where does it come from?

Who can have it?

How do you know you have it?

Saint Paul, arguably one of the greatest theological minds ever, said this about faith: it’s what saves us. Martin Luther, writing some 1500 years after the time of Saint Paul, went a little farther to say, faith alone saves us. When Paul said it, he was probably in a jail cell, locked up for preaching the Gospel, which, at that time, was equal to speaking out against the authorities. Paul didn’t have anything against the authorities. In his letter to the church at Rome, the same letter in which he wrote, faith saves us, Paul also wrote,

“Let every person be subject to the governing authorities, for there is no authority except from God, and those authorities that exist have been instituted by God. Therefore, whoever resists authority resists what God has appointed, and those who resist will incur judgment. For rulers are not a terror to good conduct but to bad. Do you wish to have no fear of the authority? Then do what is good, and you will receive its approval, for it is God’s agent for your good.”

Romans, chapter 13

Paul will go on to say that, for this same reason, everyone should pay their taxes, giving revenue to whom revenue is due, and honor to whom honor is due.

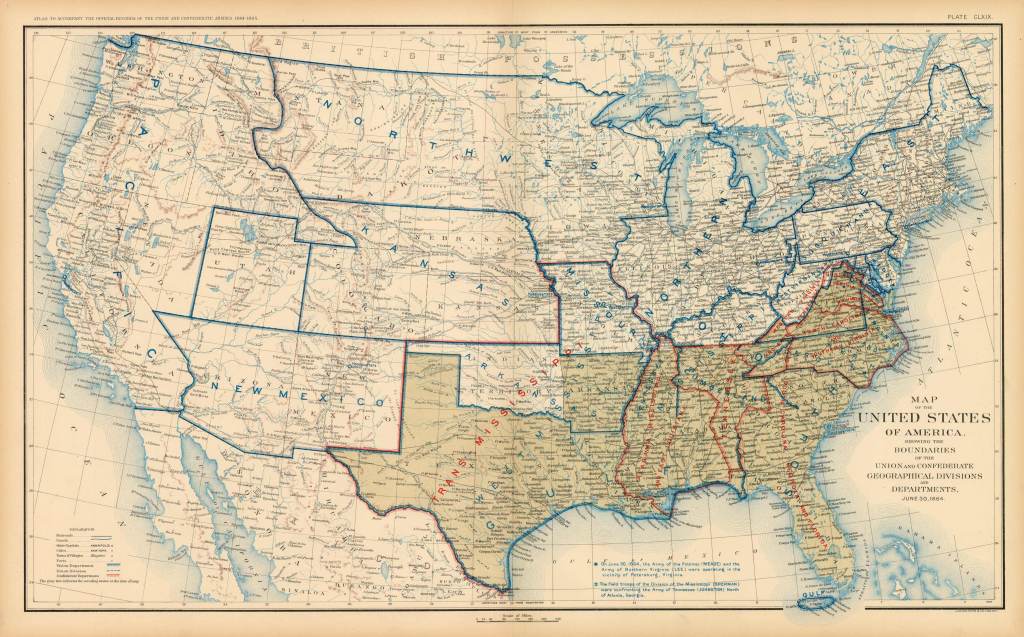

It would be easy, I suppose, to take Paul’s words as blanket approval of government. Many have taken Paul this way, as someone who equated being patriotic with being Christian. But one need not look any farther than to what happened in Germany in the 1920s, or way down south in America in the 1960s, to see the atrocities that come from Christians confusing love of country with love of God. When this happens, people who say they love Jesus, risk becoming complicit in killing people who are just like Jesus. We’re not just talking about the fact that at the time of the Holocaust in Germany, Jews made up less than 1% of the population, while Catholics and Protestants, those who called themselves Christian, made up 99% of the population.[1] Nor are we just talking about the fact that in Mississippi in 1964, members of the Klu Klux Klan, White Knights as they were called, responsible for lynching black people and burning crosses, met in the churches where their leaders attended on Sundays. What we’re talking about is how easily we scare in a world where faith hardly ever seems like enough to save us.

What we’re talking about is how easily we scare in a world where faith hardly ever seems like enough to save us.

It must be one of the most burned-out phrases of all time, to hear someone say: You just have to believe. It might be the first day of school, the first day on the new job, the first day without a job anymore, or the first day after the funeral, and you’re asking yourself, can I really do this? And someone says, of course you can, you just have to believe. You might be alone on the floor in your kitchen, alone in the hospital bed, alone in your car on some dark city street where you didn’t mean to go, or alone in your mind. You’re asking yourself, what if no one comes to find me? And someone says, they will, you just have to believe. The circumstances might be as pithy as trying to figure out how to pay this month’s rent, how to kick an addiction, or how to keep from always thinking the worst about yourself, others, or God. You tell yourself, things will never get better. And someone says, they will, you just have to believe.

Granted, it’s usually the person who is already standing on the other side of some rickety bridge that we ourselves have yet to cross who says this. “What if it doesn’t hold me?” we yell on over. “It will,” they yell on back. “Yes, but what if it doesn’t?” “It will, you just have to believe!” And we say in reply, “That’s easy for you to say. You’re 8, you weigh 50 pounds, and you’re already on the other side!”

We know this, faith isn’t the same for everyone. It’s not the same for everyone out there. Heck, it’s not even the same for everyone in here. Despite the fact that we have all showed up at the same church this morning, to sing the same hymns, to pray the same prayers, and hear the same word from God, we are far from the same when it comes to a great many other things, including our faith. I imagine some of us came here kicking and screaming this morning, if not on the outside than on the inside. Quite possibly, the only reason we are here is because the person beside us made us come, or asked us to come, and loving them so much, we have. For others, it’s all we can do to whisper the hymns and murmur the prayers. Recovering Catholics, washed out Baptists, we grew tired a long time ago of being told, you just have to believe, and then being told what it is that we have to believe. What does it mean to believe anyway?

When I was a child, I was taught it meant being a Christian, and that being a Christian meant having the faith of my grandparents and parents—a faith grown, kept, and passed on in tradition. When I became an adolescent, I was taught that it meant taking that faith and making it my own. So I chose to be baptized, and I prayed to ask Jesus to be my savior, which is what we did in the tradition of my family. The lesson was, being a Christian meant having faith in Jesus to save me from going to hell when I died. As a teenager, being a Christian was about showing the world through good behavior that I was a Christian. So I didn’t drink, or kiss a girl (for too long), I went to church every week, and I tried to do my best to convince anyone who was gay, Muslim, or just not Christian, that they needed my kind of faith if they wanted to be saved, too. Then, somewhere into my adult years, I woke up one day to realize my faith felt heavy to me, burdensome, without joy. I started to think about what it meant to keep faith in a Jesus who would save me from hell, but only if I asked him to. What kind of faith is that? And what kind of savior is that? And what does it mean for Christians to put their faith in someone like Jesus who was Jewish and never a Christian himself?

I woke up one day to realize my faith felt heavy to me, burdensome, without joy.

There are three things I want to give us today. The first is a word of warning, the second, a word of challenge, and the third, a word of blessing. First, a word of warning. The late Jonathan Saks, who served as Chief Rabbi of the United Jewish Congregations of Great Britain, once wrote, “The supreme religious challenge is to see God’s image in the one who is not in our image.” Because very often, what we believe about God—how we see God—comes from us having made it up. I don’t mean to sound like I’m accusing anyone of committing idolatry, but you would not have to look far to see how I’ve done it. Just check my Bible to see which pages I’ve dog-eared, and which pages are still stuck together, or check my purchases on Amazon, or survey my friends. All will tell you that I stick close to sources that support my views and ideas. And even when I do come across a new idea, I find myself trying to make it fit into an older, more comfortable idea. I have never burned any crosses, but still, my ability to keep a lid on my world says a great deal about the privilege afforded me as a white, rich man in America. None of this makes my faith better or worse than someone else’s, it’s just a reminder of how hard we must work to see God’s image in the one who is not in our image.

“The supreme religious challenge is to see God’s image in the one who is not in our image.”

Rabbi Jonathan Saks

Which brings me to the second word I want to give us, a word of challenge: a faith that turns away the hungry and hurting is no faith at all. It does no good to tell someone who is hungry, don’t worry, things will get better, you just have to believe, while you’re sitting there munching on a sandwich. Even Jesus had to learn this the hard way. In our gospel lesson for today, he is traveling through the region of Tyre and Sidon when a Canaanite woman comes up to him asking—no, begging—for him to do something to heal her tormented daughter. That she is a Canaanite is significant, for once upon a time her people were enemies with Jesus’ people. When they looked at each other, neither side saw the image of God. They saw only someone to be feared, hated, and eliminated. The Canaanite woman knows this, that she is showing up to the clubhouse where she is never going to be let in. And Jesus tells her just that. “It is not fair to take the children’s food and throw it to the dogs.” But she reminds him that he is a Jew, and his God has always been bigger than the one we imagine, bigger even than the one he imagines. His God has never let anyone, not even the dogs, go hungry.

The disciple named John, who wrote three separate letters, each of which appear towards the end of our Bible, said in his first letter: Those who do not love a brother or sister whom they have seen, cannot love God whom they have not seen. In her book, Holy Envy, Barbara Brown Taylor writes the following:

You will have your own interpretation of this teaching and others like it, but here is what it reveals to me: the same God who came to the world in the body of Jesus comes to [us] now in the bodies of [our] neighbors, because God knows that a body needs a body to make things real, and the real physical presence of [our] neighbors makes them much harder for [us] to romanticize, fantasize, demonize, or ignore than any of the ideas [we] have of them in [our] head.

If I could make my neighbors up, I could love them in a minute. I could make them in my own image, [and then tell them how wonderful they are!]. But nine times out of ten these are not the neighbors I get. Instead, I get neighbors who cancel my vote, burn trash in their yard, and shoot guns so close to my house that I have to wear an orange vest when I walk to the mailbox. They put things on their church signs that make me embarrassed for all Christians everywhere. They text while they drive, flipping me off when I pass their expensive pickup truck on the right, in spite of the fish symbol on their rear bumper.

But if you stop and think about it, what better way could there be for me to love the God I cannot see than to try for even twelve seconds to love these brothers and sisters whom I can see? What better way to shatter my custom-made image of God than to accept that these irritating and sometimes frightening people [we call neighbors] are also made in the image of God?

From her book, “Holy Envy,” (New York, NY: Harper One, 2019, pgs. 194-95) Words in bracket [ ] are mine.

Honest to God, with a faith like that, the world would not need saving, for it would be saved already.

I said I was going to give you a third word, a word of blessing. Here it is: Be the kind of Christian, the kind of person, the kind of neighbor today who leaves a trail of crumbs that lead straight to your own door. And should your neighbor ever do the same for you, don’t be afraid to follow the crumbs that lead straight to their door. For in so doing, you may discover a mercy beyond your wildest imaginations.

[1] https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-german-churches-and-the-nazi-state

A Cosmic, Holy Order

“But when his brothers saw that their father loved him more than all his brothers, they hated him and could not speak peaceably to him… They said, “Come, let us sell him to the Ishmaelites and not lay our hands on him, for he is our brother, our own flesh.” And his brothers agreed” (Genesis 37:4, 27).

Good morning again. For those of you who may not know me, my name is David. I am the pastor here. At least that’s what the sign out on the front lawn tells me. After being away on sabbatical the last eight weeks, it is good, and more than good, it is reviving, to be back here in this place with you today. To know you’re home because your name is still on the mailbox or hanging somewhere on the wall with all the other brothers and sisters who have ever come here looking to be known. What a gift. But what a gift sabbatical is as well.

For this is what sabbatical is, or at least what it’s supposed to be: gift. From the word sabbath and the biblical story of Genesis, a sabbatical is what God took on the seventh day of creation. After having worked for 6 days straight, Genesis 2 records, …and on the seventh day, God rested from all the work that he had done. In that moment, I imagine God a painter, stepping back from the canvas to get a good look at his painting. He steps back far so he can see how it all came together. How the sky meets the ocean, turning plain old blue into turquoise. How the sun and moon both manage to stay always perched in the sky, never trying to outshine each other. How the elephant sits so calmly while a funny little bird sits on its back pecking at ticks hidden away in the tangly hairs of this great, gray, gentle beast. How Adam and Eve seem to understand so easily and so well what it means to have been included last, and not first, in the painting. Be fruitful and multiply, God told them. Fill the earth, subdue it, have dominion over everything you see. Tricky words for our industrialized, American, 21st century ears to take in, but not for Adam and Eve, who must have known that when God said to subdue, God didn’t mean for them to have their way with everything, without any consideration for what would happen to them or their fellow creatures if they were to mistreat, kill, or destroy the earth.

But there are a few things we need to recall, a few things we must recall, if we are to keep from being destroyed. First, while there is no getting around the fact that in Hebrew, the word subdue does in fact mean to subdue, even to a point of getting hostile, in Genesis chapter one there is nothing worth getting hostile over. There are no nations, no borders, nothing to fight about. It’s just Adam and Eve, and short of some unruly weeds they might encounter in the back yard, they have no enemies, nothing to subdue. What does it mean, then, that God uses this word to describe what Adam and Eve are to do? Is God setting them up for things to come? Does God already know that, for as good as things are now—in the beginning—it won’t take long for things to get bad, and Adam and Eve should prepare now for that day when they will need to subdue and dominate? No, I don’t believe so.

Read the whole of Genesis chapter one and what we see is that God is not the kind of painter who just throws paint on the wall willy-nilly. Inventive, surprising, and unpredictable as God is, there is equal purpose and order to the way God goes about creating the world. God begins with darkness, and then uses the darkness to call forth light, from which comes the day, from which comes the night. On the second day of creation, God adds the sky, from which then comes the sun, moon, and stars. On the third day, the earth appears, and from the earth, fruits and vegetables, which grow in seasons made possible only by the turning of the sun and moon. Then there are the waters, which, along with the birds, come from the sky. You see how it works? Everything depends upon everything for its life, indeed for its very survival. Nothing and no one can afford to fight for dominance, or to act with intolerance and indifference towards the earth or each other. For God made us in such a way as to make it impossible for us to go it alone. We need each other. We are part of a great cosmic, holy order, what the late Frederick Buechner calls an alphabet of grace. Each of us a letter that, on its own, can be meaningless, or can be part of great meaning. This is us—an alphabet of grace, a holy order of love that must be honored, respected, and tended to as such.

Of course, we know through painful experience that sometimes, most of the time, things get out of order—we forget our place in the world. When this happens, order must be reestablished. In a word, we must subdue, and be subdued ourselves.

I thought about this and read for us a piece of the Joseph story from Genesis 37, a reminder of what can happen when things get out of order, and pride, jealousy, and fear are allowed to dominate at the front of the line. In the Joseph story, Joseph, the second youngest of 12 sons born to his father Jacob, is sold into slavery by his brothers. Here’s how it happened: Jacob, having two wives named Leah and Rachel, loved Rachel the most. But for years, Rachel could not get pregnant, and pregnancy, being a badge of honor for a woman back then, made Rachel’s barrenness a point of disdain for her and her husband. I have been cursed by God, is what Rachel told herself lying in bed each night.

For better or for worse, however, ancient Mesopotamian society provided a back-up plan for women like Rachel. If unable to become pregnant, she could give her slave woman to her husband to become pregnant for her. Which is what Rachel does; she gives her slave Bilhah to Jacob.

That Rachel even has Bilhah to give says a great deal about Jacob and Rachel. They are people of economic means in this world, and Rachel, though feeling powerless in her role as a wife and woman, uses those means to prove she is still more powerful than some. Who among us hasn’t, from time to time, done this very thing? Standing at the back of the line, we cry, I don’t belong here! Do we ever stop to think, though, about the fact that what the person directly in front of us hears in that moment is, I am better than you.

In the case of Rachel, crying out from the back of the line will only get her so far. For, in the end, any children Bilhah may have will belong to Bilhah and Jacob, not Rachel and Jacob. You see, this is not a surrogacy situation between the two women. It is simply a way for Rachel to save what little face she can.

Bilhah will have children, two boys. Much to everyone’s surprise, Rachel will wind up becoming a mother as well, giving birth to two boys of her own, Joseph and Benjamin. All told, Jacob will have 12 sons by 4 women. But here’s the rub, Rachel, whom he loves the most and only ever wanted to be with, will die first. Leah, whom he had to marry but, really, never wanted to, will live on in the book of Genesis with barely a mention. And Bilhah and Zilpah, Rachel and Leah’s slave women, they of course are never mentioned again.

In the end, what will remain is Jacob and his 12 sons. They and they alone make up the story line of 13 chapters in the book of Genesis, beginning in chapter 37 when 10 of the brothers decide to sell Joseph into slavery. The only reasons we are given for this cruel move on their part is that they see how their father loves Joseph more than them, and they hate Joseph for it. But a closer look at the story and we find, as always, there is more to it. In verse two, Joseph is in the fields helping his brothers tend the family herd. Specifically, he is said to be helping four of his brothers, the four who were born to Bilhah and Zilpah. Boy, it must have torn Joseph up to hear his father say, go help those ones. With Rachel dead, he, the favorite son of his father’s favorite wife is being made servant to the sons of the servants. Bilhah had been brought in to do what Joseph’s own mother could not. Do you think, while they were out tending the sheep, their father back in the house, the sons of Bilhah and Zilpah might have dug into Joseph about it. You know, Joseph, our mothers might have been slaves, but at least they were masterful at being women. Your mother, she wasn’t even a full woman. And you think you’re better than us, Joseph?

Then, one day, Joseph, perhaps looking to put them in their place, snitches on them to their father. What dirt Joseph had on them, we don’t know, and it doesn’t matter. The point is, in going to dad to rat out his brothers, Joseph is pushing back. He knows his father will listen to what he has to say and believe it. After all, he is the favorite son. Better than me? Ha! I’ll show my brothers who’s better.

It’s hard to say who’s to blame for the way things turn out. If Joseph had just not acted so arrogant and privileged; if his brothers had just not given in to revenge and slavery; if their mothers had just been there to tell them all to knock it off; if their dad had just loved them all the same when they were young; if they could have all just stepped back in that moment to recall the way it’s supposed to be, the way God made us—an alphabet of grace, a cosmic, holy order of love, each of us a gift, no one better than another.

Ernest Hemingway, author of Old Man and the Sea, once said, “There is no nobility in being superior to others. The only nobility is in being superior to our former self.”

In 2020, The 1619 Project was published by the New York Times. As part of the project, Khalil Gibran Muhammad reminds us in her essay titled, Sugar, that when Africans started getting bought, sold, and shipped as slaves between Great Britain, the West Indies, and the American Colonies, it wasn’t just the southern colonies who were guilty of getting involved. From 1709 to 1809, from what is now the stretch of land between Fox Point and India Point in Providence, Rhode Islanders made over a thousand voyages to Africa, procuring 106,544 enslaved persons.[1]

I’d like to think we have come a long way from our past, that we have learned the wisdom of Hemingway: “There is no nobility in being superior to others. The only nobility is in being superior to our former self.” But if you woke up today worried for a world still stuck in an old order, I offer you one final thought.

As part of my sabbatical, I spent five days back at the Society of Saint John the Evangelist, a monastic community of 11 brothers in Cambridge, Massachusetts. On my last day there, a Sunday as it would so happen, Moira, Lillian, and Rowan drove into the city to go to church with me. I think it’s safe to say, both kids were curious to see how monks live. Everyone wearing the same black habit, tied off at the waist with a simple rope. A pair of sandals on their feet. All day long they walk about not in total silence but in a quietness so practiced it feels natural; gathering to pray 5 times per day, working only to give away what they make to the poor. To the uncurious, their life together might appear boring, unproductive, irrelevant, pointless.

On the day Moira and the kids came in to meet me, it was a sunny, unusually cool July day, perfect for gathering in the monastery gardens after church for a time of fellowship hosted by the brothers. Over a glass of lemonade and a piece of zucchini bread, one of the brothers mentioned that they used to have a dog living at the monastery, a black lab who would roam about the hallways, greeting guests and stealing scraps from the kitchen. “He was systemically starved,” Brother Curtis said with a laugh and a soft, far-off look in his eyes. “Will you ever get another dog?” Rowan asked. “Some of us would like to,” said Brother Curtis, “I want one very much, but not everyone does.” Rowan was quick to make the connection. “That sounds a lot like our family, except we do have a dog. Why don’t you all just vote on getting a dog?” “Well, sometimes that can work,” Brother Curtis said with a smile, “but there are certain things you need everyone to agree on.” “You mean everyone has to say they want a dog before anyone can get one? That seems like it will never happen,” Rowan exclaimed. “No, we don’t all have to want a dog, but we do all have to agree that if we get one, we will all love the dog.”

“I really only love God as much as I love the person I love the least,” said Dorothy Day once upon a time.

If the Bible begins in Genesis with these words, In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth—an alphabet of grace, a cosmic, holy order born in love— it ends in Revelation with these words, And behold, I saw a new heaven and a new earth.

I heard someone ask a question not too long ago about why people go to church. “Do you go to be with the people you love, or do you go to love the people you are with?” Both can have their good points, and I don’t know your reason for being here today, but can we all agree that, in being here, we will all love?

And behold, I saw a new heaven and a new earth.

[1] Khalil Gibran Muhammad, from her essay, Sugar, (“The 1619 Project,” NY: The New York Times Company, 2021), p. 80, ref. The Transatlantic Slave Trade: A History, rev. ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005), 212-13.

Tale of the Tides

Ah, summer in New England, where no one lives too far from the beach.

For the record, I’m not much of a beachgoer. I prefer life under a pine tree, my feet dappling in a cool stream. Even my favorite beach chair is my favorite only because it smells like smoky campfire and bug spray. Sand between my toes, salt making my hair feel like dried pasta—it’s simply not my jam. And yet, that blue horizon line stretching my eyes out, and my mind too. “How many loves might there be in the world?” Mary Oliver once asked. Who else is out there, my whole body wants to know, just on the other side of that line, which is no line at all?

“How many loves might there be in the world?”

“On the Beach,” by Mary Oliver

If there is something I love about the beach, it’s low tide. When it’s high tide, and you’re sitting with your back almost against the parking lot and your feet almost in the water, it’s hard to imagine that in three hours there will be half-a-mile of open beach before you. I don’t know why this is so hard to imagine. The tides have been swapping places without fail for billions of years, and not just on the beaches of Cape Cod in July but also on the frozen shores of Antarctica in January. People can attest to it; if they could talk, penguins, narwhals, and seagulls could attest to it. Why then is it so hard (for me at least) to imagine that just under the cover of this dark liquid mass will soon appear a soft brown earth?