The first time I met her was right here in this room. It was a Sunday in mid-August. The thing you have to know about Sundays in mid-August is that it’s the dog days of summer. Churches might pack ‘em in on Christmas and Easter, but in August, only the faithful survive. Now some might call the “faithful” crazy, foolish, like the remnant before the flood. The sun is shining, there’s not a cloud in the sky, and everyone is heading to the beach, while the faithful stay home to build a boat. And why? Because God says it’s going to rain—hard, really hard. You’re going to get drenched, and then you’re going to get drowned. The world can be this way, and it doesn’t make a lot of sense. Frederick Buechner once described the world as the place where beautiful and terrible things happen, and sometimes all at once. That God might play a hand in the beautiful is the easy part for us. That God might also be in on the terrible, well, that’s a tougher pill to swallow. Sending so much water that it destroys not only the unjust but also the just, not only the cockroaches but also the koala bear, not only the weeds in the garden but also the tulips, not only our enemies but also our loved ones.

I can’t tell you why terrible things happen, or what hand God plays in it. What I do know is that the faithful, believing in the goodness of God in all things, build boats and show up to church in the dog days of summer. I find it’s their way of acknowledging that life is beautiful, but it can also be terrible, terrible hard. So they do what must be done to store up hope and safeguard faith for the days when the rains come. That way, no matter the hurt, no matter the pain, no matter how great the storm, when all is said and done, there will still be hope and faith.

So here I was. It was a Sunday in mid-August. In a couple months, I would be hired as Minister, but on this particular day, I was just a fill-in preacher dressed in a suit and tie. Arriving at the side-door, a woman stopped me. “Good morning. Are you new here today?” “Actually, yes, I am.” “Well, feel free to sit anywhere, just don’t sit there,” she said, pointing to a pew just inside the door, “that’s my seat.”

I won’t lie, my first thought was, who is this woman? If this is the Chair of the Welcoming Committee, she needs to work on her delivery. Who tells a visitor, “sit anywhere, just not there?”

A couple months later, I was now the Minister, and it was now mid-October. Showing back up at the door, there she was again. This time, she didn’t tell me where not to sit. Instead she told me, “You sit up there.” “Yes, thank you,” I replied, “that much I do know.” She smirked and gave me a hug and a kiss. It was only our second meeting, and my first thought was, who is this woman? If this is the Chair of the Welcoming Committee, she needs to work on her delivery. Who gives the new Minister a kiss and tells them where to sit? Wrapping her arms around me, she disarmed me. “I’m glad you came back, and that you’ve decided to stay,” she whispered in my ear.

It would take me some time before I would start to understand what she was doing there at the door every Sunday, greeting us, giving us hugs and kisses, telling us where to sit, and where not to. To be frank, I’m not still not sure I understand it completely, but two things, I think, I have come to figure out. One, she was being helpful. Truly. She was saying to us, “If you sit down and realize you forgot a bulletin, just come on back, I’ll be right here. If you need some assistance with the elevator, come on back, I’ll be right here. If you need to know where the bathrooms are, come on back, I’ll be right here. If you can’t find a seat, or you don’t want to sit alone, come on back, I’ll help you find one. You can’t have my seat, but you can sit beside me, I’ll be right here. If you need a hug, or two, or three, come on back, I’ll be right here.”

It is one of the great tragedies of our existence that we have given up on finding hope. Author Wendell Berry once wrote, “I can’t give anybody hope. Hope has to come out of you… To find something worth hoping for is a very good place to start. There are things worth hoping for, there are good people, this is a still a very beautiful world… We all need to find things we love to do, and love them. We’ve been talked out of love, mercy, kindness. We’ve got to take those things back.”

Which brings us to the second thing I believe she was doing at the door every Sunday: she was taking back hope…for herself. You see, she walked in and out of a few doors of her own in her lifetime. For as many of us who knew her as the woman at the door every Sunday, showing up even in mid-August, who knew where her own seat was, she—how shall I put this?—she seemed to struggle to find her own place in this world at times. She chased after love a few times, caught it a couple times; got married twice; was a mother several times over; was widowed more than once; and after her final widowing admitted to me that she never quite knew how to live alone in this world. But who does?

For all of this, she could be restless, particular, unforgiving, and plain old hard to get along with at times. For sure, she walked her way in and out of a few doors in her lifetime, searching for…what was she searching for? Hope? A boat to ride out the storm on? A seat to call her own.

I thought about this and read for us Psalm 84 and First Corinthians 13. From Psalm 84, the song of a pilgrim looking for a home and finding one:

My soul longs, indeed it faints,

for the courts of the Lord; my heart and my flesh sing for joy

to the living God. Even the sparrow finds a home

at your altars, O Lord of hosts. Happy are those who live in your house,

ever singing your praise. I would rather be a doorkeeper in the house of my God

than live in the tents of the wicked.

And from First Corinthians chapter 13, a word about what will remain when all we are is…remains:

As for prophecies, they will come to an end; as for words, they will cease; as for knowledge, it will come to an end. For we know only in part, and we speak only in part, but when the complete comes, the incomplete will come to an end. For now we see only a reflection, as in a mirror, but then we will see face to face. Now I know only in part; then I will know fully, even as I have been fully known. And now faith, hope, and love remain, these three, and the greatest of these is love.

One of the last times I saw her was about a month ago. We were, as you might imagine, right here in this room. It was a Sunday morning at 10 a.m. The Prelude was over and I was trying to get the service started, only she was still standing up—not in her usual spot at the side-door, but at the way back there. For about 15 minutes, she’d been making her way around the room giving hugs and kisses to everyone, still disarming the visitors. She hadn’t been in church for a few weeks. I guess you could say she was making up for lost time.

I said “Good morning,” and everyone quieted down. Everyone that is except her. She just kept right on working the room. “Hold on,” she said to me, “I’m coming.” We all waited while she hobbled her way over to her seat. It was, of course, empty and waiting for her. “Okay, you can start now.”

I honestly can’t explain what happened next. It was something like the sound of laughter welling up from the masses, like a feeling of hope, of joy in knowing that an old woman had finally given up her place in the doorway. She no longer had to play the doorkeeper. She had found her way inside to that place where love is all there is and love is all we are.

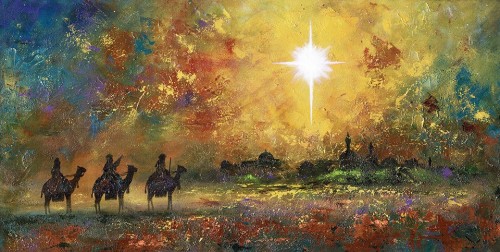

It happened again a little over a month ago. This time it was God who came to stand in the doorway. “Good morning Helen.” “Hold on,” she said even to God, “I’m coming.” “No worries, no worries at all,” said God in reply, “I’ll wait.” But no sooner had God said this and there she was, right in the doorway. And God reached out and gave her the gentlest of embraces.

Rest easy, our friend. Love remains.